Talbot County,

Maryland

HISTORY - YOUNG FREDERICK DOUGLASS

1817 - 1836

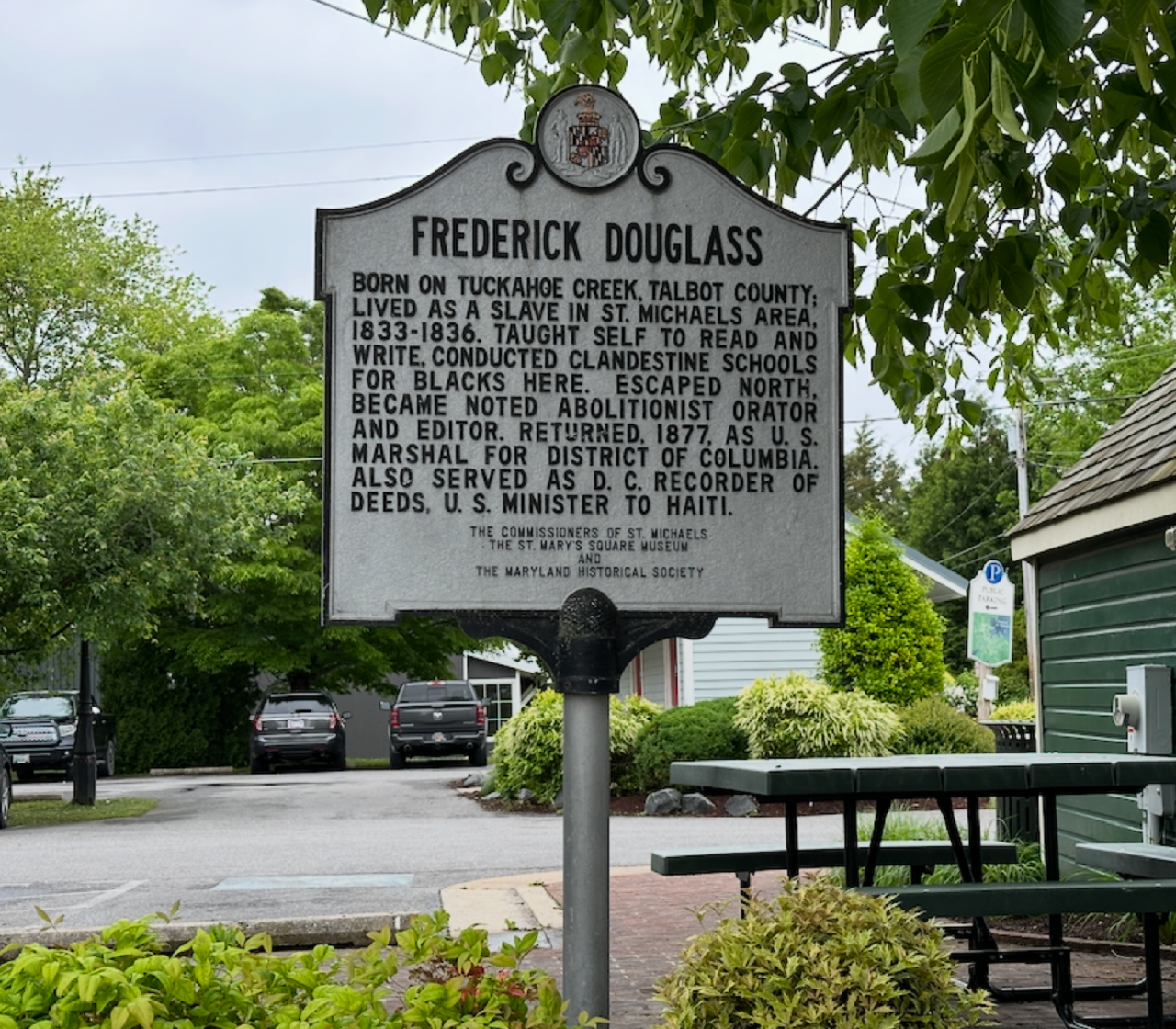

Frederick Douglass (born Frederick Augustus Washington Bailey, c. February 1817 or February 1818 – February 20, 1895) was an American social reformer, abolitionist, orator, writer, and statesman. He became the most important leader of the movement for African-American civil rights in the 19th century.

After escaping from slavery in Maryland in 1838, Douglass became a national leader of the abolitionist movement in Massachusetts and New York, during which he gained fame for his oratory and incisive antislavery writings.

Douglass wrote three autobiographies, describing his experiences as an enslaved person in his Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, an American Slave (1845), which became a bestseller and was influential in promoting the cause of abolition, as was his second book, My Bondage and My Freedom (1855). Following the Civil War, Douglass was an active campaigner for the rights of freed slaves and wrote his last autobiography, Life and Times of Frederick Douglass. First published in 1881 and revised in 1892, three years before his death, the book covers his life up to those dates.

Douglass was proud to be an Eastern Shoreman. He wrote that it's important to know about a person's place of birth "if, indeed, it be important to know anything about him". Although Douglass at one time wrote an unflattering description of his birthplace, he later told an audience in Baltimore, "I am an Eastern Shoreman, with all that name implies. Eastern Shore corn and Eastern Shore pork gave me my muscle. I love Maryland and the Eastern Shore!" When he visited the former slave plantation on the banks of the Tuckahoe River in Talbot County, where he was born, he scooped soil from the spot into his hands and later told an audience that he would carry back to Cedar Hill, his home in Washington D.C. "some of the very soil on which I first trod."

Aaron Anthony, with his daughter and his slaves lived in this house.

Douglass faced the worst depths of chattel slavery between 1834 and 1836 in the area west of St. Michaels known as Bayside or the Bay Hundred. Bayside farms were smaller than local plantations and were often occupied by tenant farmers using hired labor, both enslaved and free.

At the age of 6, Douglass was separated from his grandparents and moved to the Wye House plantation, where Aaron Anthony worked as overseer.[13] After Anthony died in 1826, Douglass was given to Lucretia Auld, wife of Thomas Auld, who sent him to serve Thomas' brother Hugh Auld and his wife Sophia Auld in Baltimore.

From the day he arrived, Sophia saw to it that Douglass was properly fed and clothed, and that he slept in a bed with sheets and a blanket.[24] Douglass described her as a kind and tender-hearted woman, who treated him "as she supposed one human being ought to treat another."[25] Douglass felt that he was lucky to be in the city, where he said enslaved people were almost freemen, compared to those on plantations.

When Douglass was about 12, Sophia Auld began teaching him the alphabet. Hugh Auld disapproved of the tutoring, feeling that literacy would encourage enslaved people to desire freedom. Douglass later referred to this as the "first decidedly antislavery lecture" he had ever heard. "'Very well, thought I,'" wrote Douglass. "'Knowledge unfits a child to be a slave.' I instinctively assented to the proposition, and from that moment I understood the direct pathway from slavery to freedom."

Under her husband's influence, Sophia came to believe that education and slavery were incompatible and one day snatched a newspaper away from Douglass. She stopped teaching him altogether and hid all potential reading materials, including her Bible, from him. In his autobiography, Douglass related how he learned to read from white children in the neighborhood and by observing the writings of the men with whom he worked.

Douglass continued, secretly, to teach himself to read and write. He later often said, "knowledge is the pathway from slavery to freedom."

When Douglass was recalled to St. Michaels by Hugh Auld’s brother Thomas Auld, he was 15, a fast-growing teenager. In urban Fells Point, he had the ability to fraternize with black and white friends, attend church, improve his reading, and move around the city when not at work in the shipyard.

In contrast, St. Michaels was a depressed, poor community with violent racism ingrained in local customs. In the fall of 1833, Douglass worked with several others in the community to start a Sabbath school for black students.

Not only was the school broken up by a mob at its second meeting, it was also the last straw for Thomas Auld. Shortly after the school incident, Auld rented Douglass to Bayside farmer Edward Covey, infamous for his ability to break the spirits of rebellious slaves. In the isolated Bayside, Douglass became a man and determined he would be free.

PM - FREDERICK DOUGLASS DRIVING TOUR

3 Sites

.4 miles

9 minutes (walking time)

4 Sites

32 miles

45 minutes (drive time)

Locations:

- St. Michaels, MD

- Sherwood, MD

- Wittman, MD

- Easton, MD

SITE

The Mitchell House is the small white cabin on the Chesapeake Bay Maritime Museum grounds. The cabin is open daily to Museum visitors. Admission may be purchased at the front gate ($20 /adult).

HISTORY

Two years older than Frederick, Eliza Bailey Mitchell was the closest sibling to Douglass. They maintained a lifelong relationship. The two of them had shared experiences under Thomas and Rowena Auld and, as Douglass later claimed, it was Eliza who taught him the art of survival in the face of hunger and abuse. Eliza and her two children were sold by Thomas Auld to her free husband, Peter Mitchell, in 1836 for $100 (a debt which they both worked for almost five years to repay). Peter Mitchell and his brother James were highly esteemed farm managers for the Hambleton family.

Eliza Mitchell was matriarch to many generations of the Mitchell family in St. Michaels and the surrounding area. Her great-grandson James E. Thomas became the first African-American elected to the town commission in St. Michaels and the first elected president of that body. The Mitchell home originally stood on Lee Street on land subdivided from Perry Cabin by the Hambletons. The house was slated for demolition and Commissioner Thomas was a leading force to save it by relocation to the Museum. While at the museum, be sure to see the log canoes and the Edna Lockwood, a 19th century bugeye under restoration. The canoe Frederick Douglass planned to take from William Hambleton would have resembled a cross between a modern racing log canoe and a bugeye.

SITE

St. Michaels on Talbot Street (Maryland Route 33) at Mill Street

Parking - Use the Mill Street lot to park and read the historical marker located in the small roadside park. Walk one block south to the southeast corner of Talbot and Cherry Streets to begin your tour.

HISTORY

Thomas Auld kept a store on this corner and lived in the block behind it, toward the harbor. The site is now a bakery. Auld scrambled to make ends meet.

He rented the store and a contract to serve as postmaster helped maintain some year-round income. In 1833, Auld was married to his second wife, 22-year-old Rowena Hambleton, daughter of Bayside farmer William Hambleton. Rowena’s youth didn’t equip her to manage a household or act as stepmother to 12-year-old Amanda Auld, Douglass’s friend from their early childhood on the Lloyd plantation.

Rowena attempted to run her household through meanness and stinginess while Thomas Auld deployed the lash with an inconsistency that bred disrespect in his slaves. Hunger was ever-present Douglass wrote of “the brutalizing effects of slavery upon both slave and slaveholder”..

There were four slaves of us in the kitchen, and four whites in the great house — Thomas Auld, Mrs. Auld, Haddaway Auld, (brother of Thomas Auld,) and little Amanda. The names of the slaves in the kitchen, were Eliza, my sister; Priscilla, my aunt; Henny, my cousin; and myself. There were eight persons in the family. There was, each week, one half bushel of corn-meal brought from the mill; and in the kitchen, corn-meal was almost our exclusive food, for very little else was allowed us…This allowance was less than half the allowance of food on Lloyd’s plantation.

Douglass goes on to describe his strategy to find enough food: [He spelled Hambleton as Hamilton.]

One of my greatest faults, or offenses, was that of letting [Auld’s] horse get away, and go down to the farm belonging to his father-in-law. The animal had a liking for that farm, with which I fully sympathized. Whenever I let it out, it would go dashing down the road to Mr. Hamilton’s, as if going on a grand frolic. My horse gone, of course I must go after it. The explanation of our mutual attachment to the place is the same; the horse found there good pasturage, and I found there plenty of bread. Mr. Hamilton had his faults, but starving his slaves was not among them. He gave food, in abundance, and that, too, of an excellent quality. In Mr. Hamilton’s cook—Aunt Mary—I found a most generous and considerate friend. She never allowed me to go there without giving me bread enough to make good the deficiencies of a day or two.

— Frederick Douglass, My Bondage and My Freedom

SITE

Lowes Wharf Rd, Sherwood, MD 21665

GPS Coordinates - 38.76569, -76.32731

HISTORY

Haddaway’s Ferry ran from here to Annapolis and brought the mail for Talbot County and points north since Colonial days. It is here that steamers of Methodist camp meeting attendees from Baltimore arrived in the hot summers of the 1830s. You can park and look across the Chesapeake Bay as you contemplate Douglass’s most important words from his time on the Bayside of Talbot County. From the waters before you he found his resolve to self-liberate and his resolve to see an end to slavery for all people.

I shall never be able to narrate the mental experience through which it was my lot to pass during my stay at Covey’s. I was completely wrecked, changed and bewildered; goaded almost to madness at one time, and at another reconciling myself to my wretched condition. …

Our house stood within a few rods of the Chesapeake Bay, whose broad bosom was ever white with sails from every quarter of the habitable globe. Those beautiful vessels, robed in purest white, so delightful to the eye of freemen, were to me so many shrouded ghosts, to terrify and torment me with thoughts of my wretched condition. I have often, in the deep stillness of a summer’s Sabbath, stood all alone upon the lofty banks of that noble bay, and traced, with saddened heart and tearful eye, the countless number of sails moving off to the mighty ocean. The sight of these always affected me powerfully. My thoughts would compel utterance; and there, with no audience but the Almighty, I would pour out my soul’s complaint, in my rude way, with an apostrophe to the moving multitude of ships:–

You are loosed from your moorings, and are free; I am fast in my chains, and am a slave! You move merrily before the gentle gale, and I sadly before the bloody whip! You are freedom’s swift-winged angels, that fly round the world; I am confined in bands of iron! O that I were free! …

I have only one life to lose. I had as well be killed running as die standing. Only think of it; one hundred miles straight north, and I am free! Try it? Yes! God helping me, I will. It cannot be that I shall live and die a slave. I will take to the water. … Let but the first opportunity offer, and, come what will, I am off. Meanwhile, I will try to bear up under the yoke. I am not the only slave in the world. Why should I fret? I can bear as much as any of them. Besides, I am but a boy, and all boys are bound to some one. It may be that my misery in slavery will only increase my happiness when I get free. There is a better day coming.

— Frederick Douglass, My Bondage and My Freedom

SITE

New St. Johns United Methodist Church

9123 Tilghman Island Rd,

Wittman, MD 21676

From the church parking lot, you can see the fields of the Covey Farm and the broad Chesapeake Bay beyond. As Douglass described, the site is midway between the landmarks of Kent Point and Poplar Island.

HISTORY

On New Year’s Day 1834, when Douglass completed the seven-mile walk from St. Michaels to Covey’s farm, he was filled with dread as he recalled the stories he had heard about Covey’s cruelty and frequent use of the whip. It wasn’t long before Douglass found out for himself how terrible Covey could be. The young slave was sent into the woods (behind this church) for a load of wood behind a team of unbroken oxen, with disastrous results and vicious punishment to follow.

This is also the scene of the weeklong Bayside camp meetings, which drew several steamers from Baltimore. In the camp meeting, Douglass observed Thomas Auld experience a conversion, become an exhorter, and yet continue to starve and whip half the members of his household. Religious hypocrisy among the slaveholders of the white Methodist church of the 1830s is a theme in all three Douglass autobiographies. Covey was also known for wearing out knees with daily prayers, “as strict in the cultivation of piety, as he was in the cultivation of his farm.”

However, it was here that Douglass came into his own when he defeated Covey in a much-celebrated fistfight. In Douglass’s own words, “This battle with Mr. Covey … was the turning point in my life as a slave … I was NOTHING before: I WAS A MAN NOW.” — My Bondage and My Freedom.

As you proceed to Site #4, note the intersection of Pot Pie Road in Wittman. The road leads to Pot Pie Neck, where Douglass’s friend Sandy Jenkins procured a root offered as a talisman. Douglass had the root in his pocket during his fight with Covey.

SITE

Pull to the roadside 0.15 mile past Broad Creek Road. after Melanie Drive, when you see Old Martingham Road

GPS Coordinates - 38.80792, -76.23903

HISTORY

Old Martingham, to your left on the Miles River, was the seat of the Hambleton family since 1663. The Hambleton family was important in the War of 1812. In Douglass’s time, a large contingent of brothers and sisters controlled most of the land from Emerson Point to Perry Cabin in St. Michaels.

Look to the right and you can see Broad Creek, part of the Choptank River with the abandoned train bridge crossing the creek. (Douglass rode a train across this bridge on his last visit to Talbot County in 1893). The farmland on the Broad Creek side is the site of the Freeland Farm, where young Douglass was hired out from Jan. 1, 1835 to spring 1836. William Freeland’s wife was one of the Hambleton sisters.

“I found myself in congenial society, at Mr. Freeland’s,” Douglas wrote. “There were Henry Harris, John Harris, Handy Caldwell, and Sandy Jenkins.” Douglass considered William Freeland to be a “well-bred southern gentleman … the best master I ever had until I became my own master.” During his time at the Freeland farm, Douglass learned that he was gaining a reputation among the whites as a troublemaker and among the blacks as a hero and leader. He was quick to take advantage of his role as a leader by organizing another school for blacks, but this time the school was kept secret.

On New Year’s Day, 1836, Douglass resolved that this was the year he would become free and began planning his escape. On Easter weekend, with the branches of the Hambleton family gathered at Old Martingham, he and four others (including his uncle Henry Bailey) would take one of William Hambleton’s two sailing log canoes from Emerson Point, round Kent Point and head up the Bay. It would take a full crew to handle the vessel. William Hambleton got wind of the plot. Sandy Jenkins (the “root man”) became frightened and was suspected of leaking some detail. On the morning of their planned escape, they were arrested and forced to walk more than 20 miles tied behind a mounted horse to the jail in Easton. Word spread quickly; at every village along the way, the men were jeered and harassed. Tour #4 includes the site of the Easton jail where Douglass spent a harrowing week, uncertain of his fate.

SITE

26080 Bruffs Island Rd

Eston, MD 21601

Wye House is located on the Eastern Shore of Maryland. It is privately owned and not open to the public. The main house, its outbuildings, and surrounding acreage compose a plantation originally established in the 17th century.

Wikipedia Historical

Frederick Douglass Heritage

( for Tappers Corner) Easternshore.com

People of Wye House - searchable database of the enslaved people of the Wye House Plantation between 1770 and 1826

Society of Architectural Historians

Clio - historical property database

National Gallery of Art - Early American Landscape Design

HISTORY

The Wye plantation was created in the 1650s by a Welsh Puritan and wealthy planter, Edward Lloyd. Between 1780 and 1790, the main house was built by his great-great-grandson, Edward Lloyd IV, using the profits generated by the forced labor of enslaved people. It is cited as an example between the transition of Georgian and Federal architecture, which is attributed to builder Robert Key. Nearby the house is an orangery, a rare survival of an early garden structure where orange and lemon trees were cultivated, and which still contains its original 18th-century heating system of hot-air ducts. During its peak, the plantation's owners enslaved more than 1,000 people to work lands that totaled more than 42,000 acres (17,000 ha). Though the land has shrunk to 1,300 acres (530 ha) today, it is still owned by the descendants of Edward Lloyd, now in their 11th generation on the property.

Frederick Douglass was enslaved on the plantation, from around the ages of seven and eight, and spoke extensively of the brutal conditions of the plantation in his autobiography, Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, an American Slave.

When Frederick Douglass was 7 or 8 years old he was taken by his grandmother, Betsey Bailey, to the Great House in the Wye Plantation about twelve miles from his birthplace, Holmes Hill Farm. Here Douglass was left on his own for the first time. It was common practice to bring young slaves who were too young to work in the plantations to the main house to do house and yard work. In his autobiographies he describes how for the first time in his life he experienced the brutal treatment of slaves by Aaron Anthony. Young Frederick Douglass lived in this house less than a year before he was given to the Auld family in Baltimore as a companion to their toddler son, Thomas.