St. Louis,

Missouri

Featuring - Dred Scott, Ulysses S. Grant, William T. Sherman

SITE

Locust St & N Broadway,

St. Louis, MO 63102

HISTORY

After Sherman returned from Louisiana, there was a letter from his old friend, Major H.S. Turner, offering him a position as president of the Fifth Street Railroad in St. Louis, Missouri. Sherman wrote back to accept the position in St. Louis before heading to Washington to see his brother. On April 1, 1861, Sherman moved his family into a rented house located on Locust Street between Tenth and Eleventh Streets. On May 14, 1861, William T. Sherman received word that he had been appointed Colonel, Thirteenth Regular Infantry and was needed in Washington immediately.

SITE

Coordinates - 38.62632, -90.18848

on Fourth Street between Chestnut and Pine Streets in St. Louis, Missouri 63101

the Planter's House Hotel faced east on the west side of 4th Street occupying the block between Chestnut and Pine Streets

The construction of the 300-room, four story hotel began in 1837. Planter's House Hotel was four stories tall and had 300 rooms. The hotel was decorated with rich carpets and paintings and the cutlery was made to order in England, with the hotels' initials engraved on each piece. Planter's Punch was invented at the hotel bar. The hotel was damaged by fire and closed in 1887. Eventually, the damaged building was torn down in 1891. Mary Bartley described the hotel in her book, “St. Louis Lost." Begun in 1837 and designed by Henry Spence, the new 300-room, four-story hotel was located at Fourth and Pine Streets, removed from the hurly-burly and odor of the riverfront.

It had a classic, dignified exterior and shops and offices at the ground level. There was a huge main dining room, and three additional restaurants were associated with it. The grand ballroom featured decorative details copied from the Temple of Erectheus in Athens, Greece. The Planter's House Hotel was considered the finest in the West and was seen by civic leaders as a symbol of the new St. Louis. It became the gathering place for politicians and businessmen and was the byword for luxury and good service. A room cost $4.25 per person per day ($139.09 in 2024), and the rate included four sumptuous meals. The trustees leased the facility to various operators over the years for the then-considerable sum of $7,000 per month ($229,085.94 in 2024). Some notable residents of the hotel were Jefferson Davis, Abraham Lincoln, Andrew Jackson, U.S. Grant, and William F. Cody. Charles Dickens also stayed at the hotel and wrote favorably about it.

Planter’s Punch

The September 1878 issue of the London magazine Fun listed the recipe as follows:

A wine-glass with lemon juice fill,

Of sugar the same glass fill twice

Then rub them together until

The mixture looks smooth, soft, and nice.

Of rum then three wine glasses add,

And four of cold water please take. A

Drink then you'll have that's not bad—

At least, so they say in Jamaica.

HISTORY

A meeting that ultimately kept Missouri in the Union during the Civil War occurred at the Planter's House Hotel on June 11, 1861. Gov. Claiborne Jackson and Gen. Sterling Price, representing secession, met with Col. Nathaniel Lyon and Frank Blair. Just ten days before the meeting, Nathaniel Lyon had been appointed a Brigadier-General of Federal volunteers and placed in command of all Federal forces in the State of Missouri. After meeting for four or five hours, Brigadier-General Nathaniel Lyon stood up, declared war on Jackson and Price, and stormed out of the meeting. Over the next several days, Lyon mobilized his forces, ultimately leading to the Battle of Boonville and sending the sitting Missouri Governor into exile.

SITE

11 N 4th St,

St. Louis, MO 63102

The Old Courthouse is part of the Jefferson National Expansion Memorial that is operated by the National Park Service. The Old Courthouse was the site of the first two trials of the pivotal Dred Scott case in 1847 and 1850. Each year on New Year's Day, it was the custom in St. Louis to hold a public auction of slaves at the Old Courthouse from the steps on which you are standing. The slaves being auctioned belonged to estates that needed to be settled by the State of Missouri. If a “fair market value” could not be obtained, these estate slaves would be held in the county jail until New Year's Day. The last of these public slave auction took place on the steps of the east entrance on January 1, 1861. Seven slaves had been brought to be auctioned from the steps. Over two thousand people had shown up in order to put an end to the slave auction. Whenever the auctioneer asked for a bid, the crowd shouted, “two dollars, two dollars,” or some other ridiculously low bid over and over. After about two hours of this, the auctioneer gave up and took the slaves back to the jail. This was the last time the auction was ever held on the Old Courthouse steps.

Dred Scott Heritage Foundation → Dred Scott Lives

HISTORY

One of the most important cases ever tried in the United States was heard in St. Louis' Old Courthouse. Dred Scott v. Sandford was a landmark decision that helped changed the entire history of the country. The Supreme Court decided the case in 1857, and with their judgment that the Missouri Compromise was void and that no African-Americans were entitled to citizenship, hastened the Civil War which ultimately led to freedom for the enslaved people of the United States. In 1846, having failed to purchase his freedom, Scott filed a freedom suit in St. Louis Circuit Court. Missouri precedent, dating to 1824, had held that slaves freed through prolonged residence in a free state or territory, where the law provided for slaves to gain freedom under such conditions, would remain free if returned to Missouri. The doctrine was known as "Once free, always free". Scott and his wife had resided for two years in free states and free territories, and his eldest daughter had been born on the Mississippi River, between a free state and a free territory.

Facts of the Case

Dred Scott was a slave in Missouri. From 1833 to 1843, he resided in Illinois (a free state) and in the Louisiana Territory, where slavery was forbidden by the Missouri Compromise of 1820. After returning to Missouri, Scott filed suit in Missouri court for his freedom, claiming that his residence in free territory made him a free man. After losing, Scott brought a new suit in federal court. Scott's master maintained that no “negro” or descendant of slaves could be a citizen in the sense of Article III of the Constitution.

Question

Was Dred Scott free or a slave?

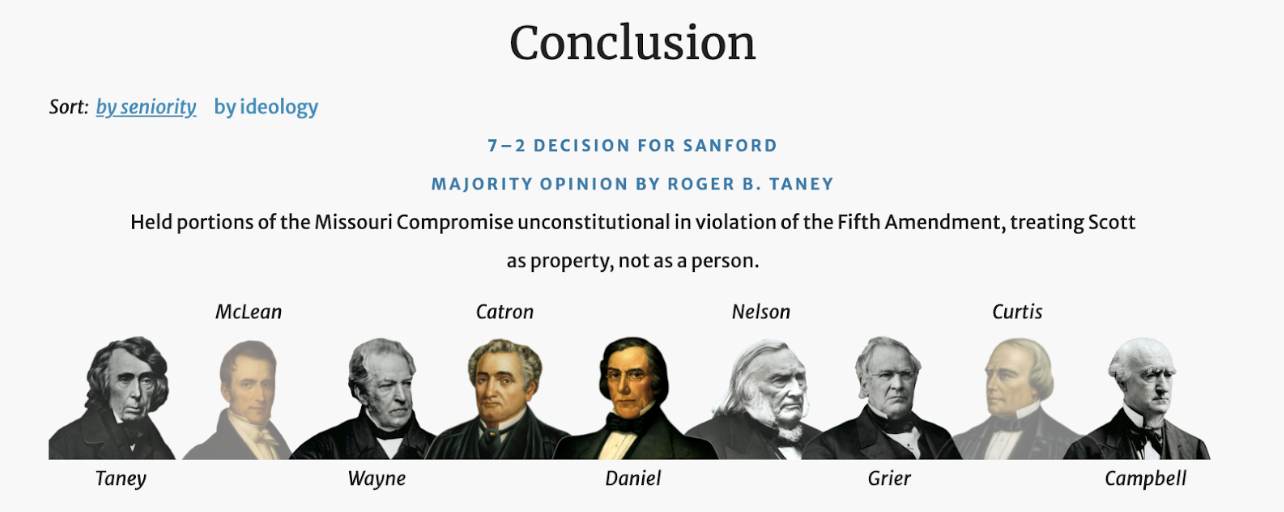

Conclusion

The majority held that “a negro, whose ancestors were imported into [the U.S.], and sold as slaves,” whether enslaved or free, could not be an American citizen and therefore did not have standing to sue in federal court. Because the Court lacked jurisdiction, Taney dismissed the case on procedural grounds. Taney further held that the Missouri Compromise of 1820 was unconstitutional and foreclosed Congress from freeing slaves within Federal territories. The opinion showed deference to the Missouri courts, which held that moving to a free state did not render Scott emancipated. Finally, Taney ruled that slaves were property under the Fifth Amendment, and that any law that would deprive a slave owner of that property was unconstitutional. In dissent, Benjamin Robbins Curtis criticized Taney for addressing the claim’s substance after finding the Court lacked jurisdiction. He pointed out that invalidating the Missouri Compromise was not necessary to resolve the case, and cast doubt on Taney’s position that the Founders categorically opposed anti-slavery laws. John McLean echoed Curtis, finding the majority improperly reviewed the claim’s substance when its holding should have been limited to procedure. He also argued that men of African descent could be citizens because they already had the right to vote in five states.

Impact

The newspaper coverage of the court ruling, and the 10-year legal battle raised awareness of slavery in non-slave states. The arguments for freedom were later used by U.S. President Abraham Lincoln. The words of the decision built popular opinion and voter sentiment for his Emancipation Proclamation and the three constitutional amendments ratified shortly after the Civil War: The Thirteenth, Fourteenth and Fifteenth amendments, abolishing slavery, granting former slaves' citizenship, and conferring citizenship to anyone born in the United States and "subject to the jurisdiction thereof" (excluding subjects to a foreign power such as children of foreign ambassadors).

SITE

Coordinates - 38.624617, -90.190450

503-437 Walnut St,

St. Louis, MO 63102

HISTORY

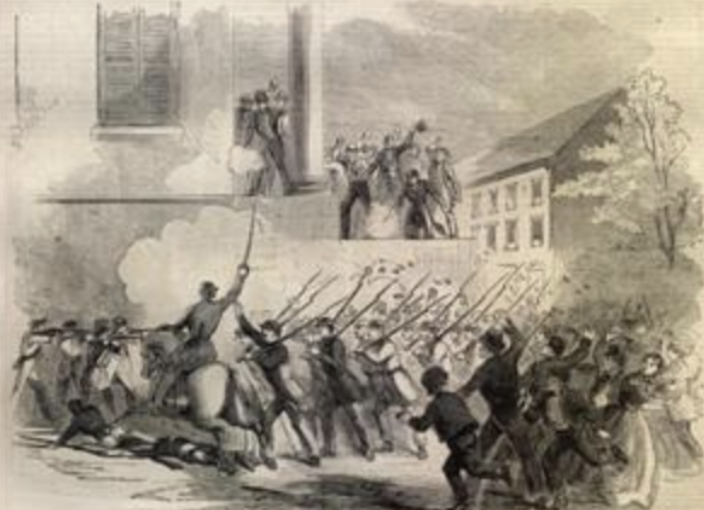

On May 11, 1861, the day after the Camp Jackson Affair, the Fifth Regiment, US Reserve Corps was attacked by a civilian mob near the corner of Fifth (modern day Broadway) and Walnut Streets. Saint Louis was in an uproar over what had occurred at Camp Jackson. The Fifth Regiment of the U. S. Reserve Corps, Colonel Charles G. Stifel, commanding, had just been mustered into service by Nathaniel Lyon. On Saturday afternoon, May 11th, the Fifth Regiment collected their arms at the St. Louis Arsenal and set off marching up Fifth street to return to their headquarters at Stifel's Brewery. As they marched past the intersection of Fifth and Walnut Streets, they were fired upon by a mob. The Federal volunteers returned fire. Two of the Federal volunteers were killed along with six of the civilians.

SITE

SW corner of Tucker Blvd &, Market St,

St. Louis, MO 63103

The statue General Ulysses S. Grant is a public tribute to Grant, who resided in St. Louis for six years. While here, he met and married Julia Dent and unsuccessfully farmed the land on Gravois, known today as Grant’s Farm. Grant held many jobs here, including selling real estate and clerking in the Customs House. He applied for the position of County Engineer, but was rejected and finally moved away to work for his father-in-law before he became the 18th President of the United States. The sculpture, a gift of the Grant Monument Association, was unveiled in 1888 on a site in the middle of 12th Street between Olive and Locust. Once the new City Hall was completed in 1898, the sculpture was moved to the south entrance. The Grand Army of the Republic, objecting that the south entrance was the ‘back door’ persisted in getting the city to appropriate $1,500 in 1915 ($46,659.65 in 2024) to move it to its current location.

DAY 2 - GRANT IN STL

SITE

Jefferson Barracks is a county park, historic site, museum district, active military installation, national cemetery, and a Department of Veterans Affairs hospital complex.

Today the site features a recreational park managed by St. Louis County, a National Cemetery managed by Veterans Affairs, and a number of museums, including the Missouri Civil War Museum.

Jefferson Barracks Historic Site

345 North Rd.,

St. Louis, MO 63125

CLOSED MON + TUE

Museums

Old Ordnance Room - Wednesday - Sunday, Noon - 4 p.m.

Powder Magazine Museum - Wednesday - Sunday, Noon - 4 p.m.

Missouri Civil War Museum

222 Worth Rd,

St. Louis, MO 63125

Located within Forest Park

** closed Monday **

Tuesday-Saturday: 10am-4pm

Sunday: 11am-4pm

Tickets - $9 /adult

Parking - Free parking for Museum guests is located behind the Museum building. Additional parking may be found along Randolph Circle, due south of the Museum.

At 22,000 square feet, the Missouri Civil War Museum is filled with over one thousand artifacts and several films throughout. Each gallery and exhibit tells a different story of Missouri in the American Civil War, from guerrillas and jayhawkers to life on the home front. The Museum also contains several galleries on the post-war era and the history of our home here at Jefferson Barracks.

Jefferson Barracks National Cemetery

2900 Sheridan Rd,

St. Louis, MO 63125

Established in 1827, Jefferson Barracks National Cemetery is the final resting place for over 200,000 veterans and their loved ones. Veterans are buried here from every American war, including the American Revolutionary War. It is also the largest burial site of Civil War soldiers in Missouri with over 16,000 Federal and Confederate soldiers. On average, there are 28 burials each day.

HISTORY

Originally an active military base from 1826 through the end of World War II, Jefferson Barracks was Ulysses S. Grant's first deployment with the U.S. Army after graduating from West Point in 1843. Despite his excellent horsemanship, he was not assigned to the cavalry after graduating from West Point, but to the 4th Infantry Regiment. Grant's first assignment was the Jefferson Barracks near St. Louis, Missouri. Commanded by Colonel Stephen W. Kearny, this was the nation's largest military base in the West. Grant was happy with his new commander but looked forward to the end of his military service and a possible teaching career.

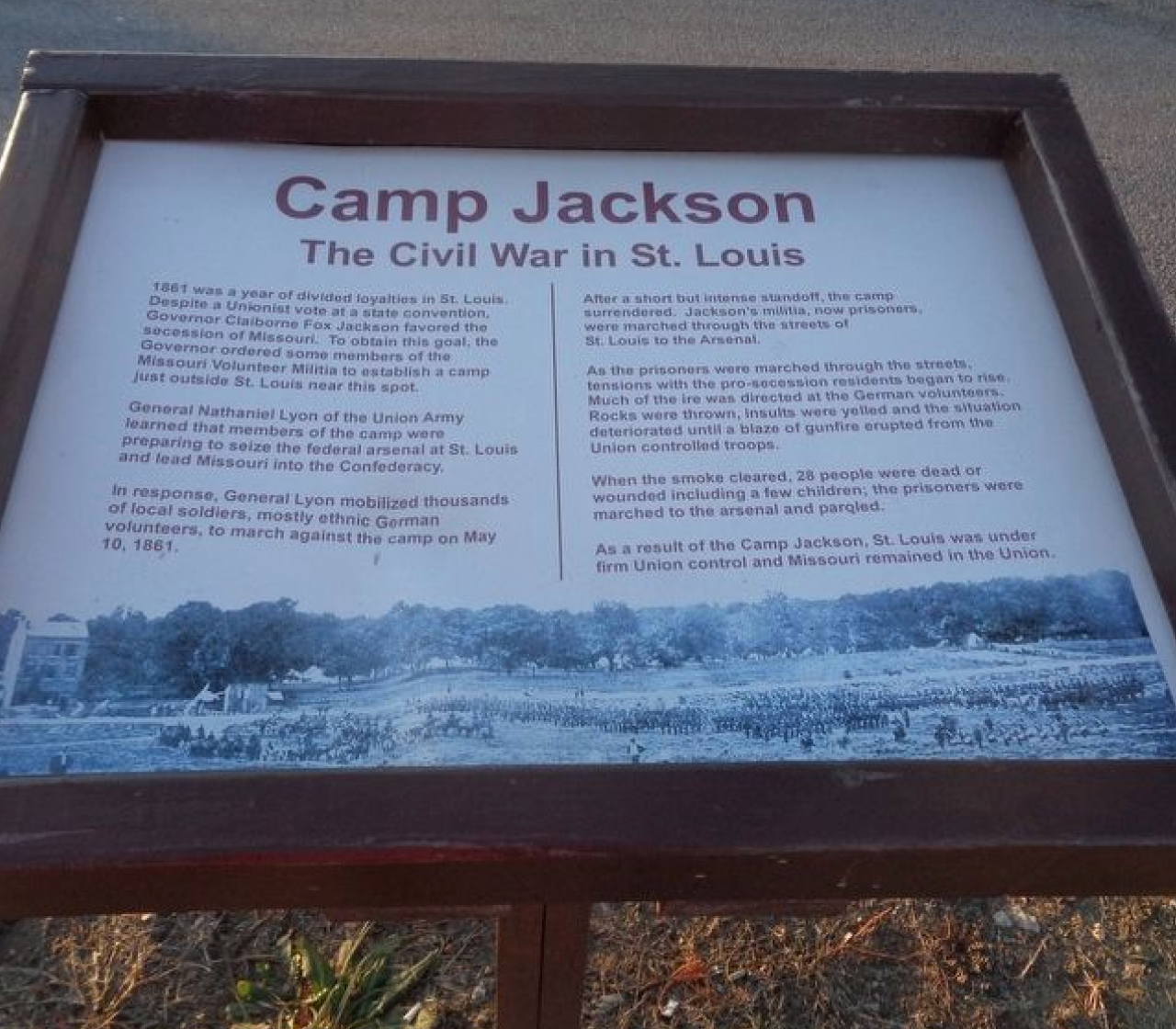

In 1861, troops from Jefferson Barracks, led by Nathaniel Lyon, participated in the "Camp Jackson Affair," which saved the St. Louis Arsenal from pro-secessionist state forces. In 1862, Jefferson Barracks was turned over to the Medical Department of the U.S. Army and became one of the largest and most important Federal hospitals in the country. Sick and wounded soldiers were brought to Jefferson Barracks by riverboat and railroad car. In 1864, Jefferson Barracks became a concentration point for the defense of St. Louis during "Price's Raid, " the last major Confederate invasion of Missouri. In 1866 a national cemetery was established at Jefferson Barracks.

On October 23, 1826, the war department declared the post to be named Jefferson Barracks in honor of President Thomas Jefferson who died six days prior to the founding of the post. The location of Jefferson Barracks near St. Louis and on the Mississippi River proved to be an excellent site for a permanent military post. Few military installations have been as important to the United States as Jefferson Barracks. The entire history of Jefferson Barracks is displayed at the Powder Magazine Museum. The post was deactivated in 1946.

SITE

7400 Grant Rd,

St. Louis, MO 63123

Daily 9am - 5pm

Parking - has its own parking lot adjacent to the Visitor Center. Parking is free, but visitors who leave to visit Grant's Farm across the street or to use Grant's Trail must remove their vehicles from the park.

Orientation Film - 22min

Park Museum - 20-30min

Tours

- offered daily,

- top of each hour btw 10am-4pm,

- 1st come 1st basis

- 20min

HISTORY

The White Haven estate was built between 1812 and 1816 and was the childhood home of Julia Dent Grant. Julia recalled fond memories of family bonding at White Haven. She later boasted that "our home was then really the showplace of the county, having very fine orchards of peaches, apples, apricots, nectarines, plums, cherries, grapes, and all of the then rare small fruits."

Frederick Fayette Dent was the father of Julia Dent Grant, father-in-law of Ulysses S. Grant, and the owner of the White Haven estate in St. Louis, Missouri for more than forty years. After meeting his wife Ellen and starting a family, the Dents moved to St. Louis by 1819. Frederick Dent became a successful merchant and land speculator. The Dents originally rented a city home but soon accumulated enough money to purchase a second home twelve miles away in the St. Louis countryside the following year. Frederick Dent called this country home "White Haven," after one of his family's plantations in Maryland. As his wealth grew, Dent added land and purchased enslaved laborers to work the property. By 1830 White Haven was 850 acres and worked by eighteen enslaved African Americans (this number would increase to thirty by 1850). Signifying his desired status as a Southern gentleman, Dent referred to himself as "Colonel," although he never held this rank during the War of 1812.

Upon graduating from the U.S. Military academy at West Point in 1843, a young officer named Ulysses S. Grant was stationed with the U.S. Army at Jefferson Barracks, a military post five miles south of White Haven. Ulysses met Julia at White Haven and they fell in love, later marrying in 1848. After serving for eleven years in the U.S. Army, Grant resigned his commission and decided to try his hand at farming at White Haven. From 1854 to 1859, the Grant and Dent families, along with enslaved African American laborers, lived and worked at White Haven. As Ulysses S. Grant rose to prominence as the victorious general of the American Civil War and the country's 18th president, his connections to White Haven continued. Grant purchased the property after the Civil War and hired a caretaker to live at the main house and manage the farm. During his presidency, Grant invested money to make the farm a horse breeding operation. He also helped design a large stable for his horses that was completed in 1871. The Grants considered retiring to White Haven at some point in time, and President Grant recalled in a speech that St. Louis was one of the only places he had ever felt a connection to. Plans changed, however, and the Grants eventually retired to New York City after the completion of their world tour in 1879. Ulysses and Julia nevertheless continued to visit White Haven on a periodic basis after the Civil War. Their last visit to the home together was in 1883, and they owned the property until a few months before Ulysses died in July 1885.

SITE

site is located on the property of a private business offering food, entertainment, and animal encounters

7385 Grant Rd,

St. Louis, MO 63123

Mon - Thu 9am - 5pm

Fri - Sun 9am - 10pm

Admission is free (donation-based), however parking costs.

Free beer

Recommend purchasing parking pass ahead of time

Cabin accessed via private tour booking only

- exclusive guided tour of Grant's Farm where you will tour the Anheuser-Busch family home, the cabin home of our 18th president of the United States, Ulysses S. Grant and an adventure through our animal park where you and your group can feed a variety of animals.

- 2 hours

HISTORY

In 1854, at age 32, Grant entered civilian life, without any money-making vocation to support his growing family. It was the beginning of seven years of financial struggles, poverty, and instability. Grant's father offered him a place in the Galena, Illinois, branch of the family's leather business, but demanded Julia and the children stay in Missouri, with the Dents, or with the Grants in Kentucky. Grant and Julia declined. For the next four years, Grant farmed with the help of Julia's slave, Dan, on his brother-in-law's property, Wish-ton-wish, near St. Louis. The farm was not successful and to earn an alternate living he sold firewood on St. Louis street corners.

In 1856, the Grants moved to land on Julia's father's farm, and built a home called "Hardscrabble" on Grant's Farm. Julia described the rustic house as an "unattractive cabin", but made the dwelling as homelike as possible. Grant's family had little money, clothes, and furniture, but always had enough food. During the Panic of 1857, which devastated Grant as it did many farmers, Grant pawned his gold watch to buy Christmas gifts. In 1858, Grant rented out Hardscrabble and moved his family to Julia's father's 850-acre plantation. That fall, after having malaria, Grant gave up farming.

That same year, Grant acquired a slave from his father-in-law, a thirty-five-year-old man named William Jones. Although Grant was not an abolitionist at the time, he disliked slavery and could not bring himself to force an enslaved man to work. In March 1859, Grant freed Jones by a manumission deed, potentially worth at least $1,000 ($37,852.41 in 2024).

Grant moved to St. Louis, taking on a partnership with Julia's cousin Harry Boggs working in the real estate business as a bill collector, again without success and at Julia's prompting ended the partnership. In August, Grant applied for a position as county engineer. He had thirty-five notable recommendations, but Grant was passed over by the Free Soil and Republican county commissioners because he was believed to share his father-in-law's Democratic sentiments.

SITE

5239 West Florissant Avenue

Saint Louis, Missouri 63115

William T. Sherman - Section 17, Lot 8

Dred Scott - Section 1, Lot 77

HISTORY

Sherman

After the war's end, Major-General William T. Sherman returned to St. Louis as the commander of the Military Division of the Missouri, returning to St. Louis in July of 1865. Sherman did not remain in St. Louis for long. In 1869, after Grant was inaugurated as the 18th President of the United States, Sherman was appointed as the General of the Army. In 1874, Sherman received permission from President Grant to move his headquarters from Washington to St. Louis, which he did in October. Sherman would retire from the army to St. Louis on November 1, 1883. William T. Sherman is buried next to his wife, Eleanor “Ellen” Boyle Ewing Sherman, in Calvary Cemetery in St. Louis, Missouri.

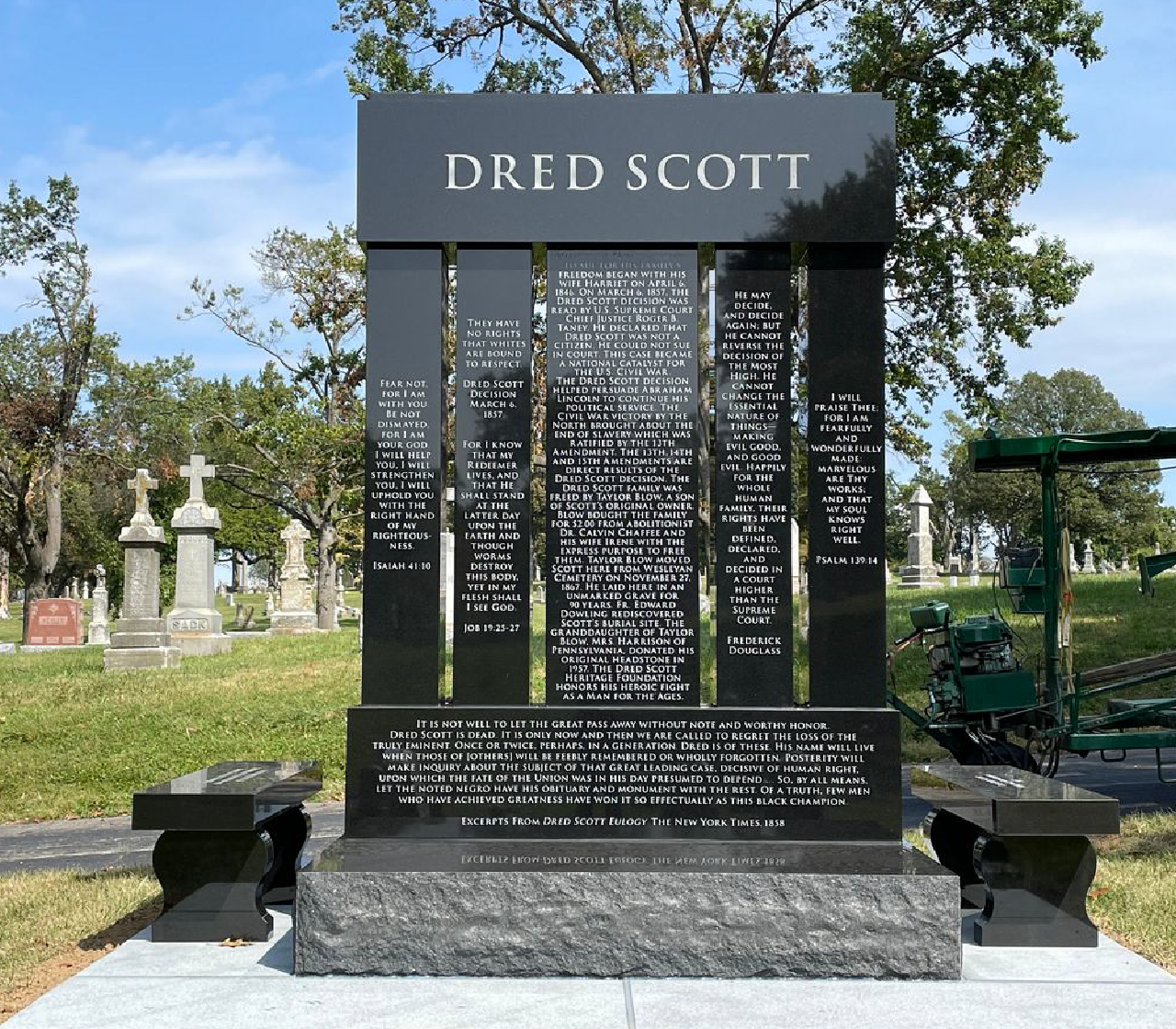

Scott

Following the ruling, the Chaffees deeded the Scott family to Republican Congressman Taylor Blow, who manumitted them on May 26, 1857. Scott worked as a porter in a St. Louis hotel, but his freedom was short-lived; he died from tuberculosis in September 1858. He was survived by his wife and his two daughters. Scott was originally interred in Wesleyan Cemetery in St. Louis. When this cemetery was closed nine years later, Taylor Blow transferred Scott's coffin to an unmarked plot in the nearby Catholic Calvary Cemetery, St. Louis, which permitted burial of non-Catholic slaves by Catholic owners. Some of Scott's family members have claimed that he was a Catholic. A local tradition later developed of placing Lincoln pennies on top of Scott's gravestone for good luck.

Harriet Scott was buried in Greenwood Cemetery in Hillsdale, Missouri. She outlived her husband by 18 years, dying on June 17, 1876. Their daughter, Eliza, married and had two sons. Their other daughter, Lizzie, never married but, following Eliza's early death, helped raise Eliza's sons (Lizzie's nephews). One of Eliza's sons died young, but the other married and has descendants, some of whom still live in St. Louis as of 2023, including Lynne M. Jackson, Scott's great-great-granddaughter, who led the successful effort to install a new towering memorial at Dred Scott's grave at Calvary Cemetery on September 30, 2023.

SITE

Coordinates - 38.665117, -90.220383

Located within Fairground Park - btw Fair Ave + N. Grand Blvd and Kossuth Ave. + Natural Bridge Ave.

Nothing of the original Benton Barracks exists on this site today.

HISTORY

Benton Barracks (or Camp Benton) was a Union Army military encampment, established during the American Civil War, in St. Louis, Missouri, at the present site of the St. Louis Fairground Park. Before the Civil War, the site was owned and used by the St. Louis Agricultural and Mechanical Association, which at the time was located on the outskirts of St. Louis. The barracks was used primarily as a training facility for Union soldiers attached to the Western Division of the Union Army.

In 1861, Major-General John C. Frémont assumed command of the Western Department of War for the Union Army. General Frémont ordered the establishment of a training barracks at the site of the St. Louis Fairgrounds. The barracks originally consisted of five buildings, 740 ft. in length and 40 ft. in width. Additionally, there was a two-story building erected for the headquarters of the Barracks Commander. The barracks could accommodate up to 30,000 soldiers.

By mid-December 1861 Sherman had recovered sufficiently to return to service under Halleck in the Department of the Missouri. In March, Halleck's command was redesignated the Department of the Mississippi and enlarged to unify command in the West. Sherman's initial assignments were rear-echelon commands, first of an instructional barracks near St. Louis and then in command of the District of Cairo.[89] Operating from Paducah, Kentucky, he provided logistical support for the operations of Grant to capture Fort Donelson in February 1862. Grant, the previous commander of the District of Cairo, had just won a major victory at Fort Henry and been given command of the ill-defined District of West Tennessee. Although Sherman was technically the senior officer, he wrote to Grant, "I feel anxious about you as I know the great facilities [the Confederates] have of concentration by means of the River and R[ail] Road, but [I] have faith in you—Command me in any way."

By 1863, Benton contained over a mile of barracks, as well as warehouses, cavalry stables, parade grounds, and a large military hospital. The hospital was built from the converted amphitheater on the fairground site and could accommodate 2,000 to 3,000 soldiers at a time. During the Civil War, under the administration of Emily Elizabeth Parsons, it was the largest hospital in the West. Parsons recorded many of her experiences at Benton Barracks in her memoir.[1] Another nurse at Benton Barracks, Belle Coddington, wrote about her memories of the hospital in an 1895 reminiscence.

SITE

Rebuilt apartment complex.

HISTORY

On April 1, 1861, Sherman moved his family into a rented house located on Locust Street between Tenth and Eleventh Streets.

SITE

38° 38.083′ N, 90° 13.55′ W. Marker is in St. Louis, Missouri. It is in Midtown. It is on North Compton Avenue south of Olive Street, on the right when traveling north. Marker is in front of an open field (on the sidewalk) and across the street from a parking garage (on Saint Louis University campus).

HISTORY

William T. Sherman was present in St. Louis when many of the key events of 1861 in Missouri took place.

Sherman remembered the situation in his memoirs:

The whole air was full of wars and rumors of wars. The struggle was going on politically for the border States. Even in Missouri, which was a slave State, it was manifest that the Governor of the State, Claiborne Jackson, and all the leading politicians, were for the South in case of a war. The house on the northwest corner of Fifth and Pine was the rebel headquarters, where the rebel flag was hung publicly, and the crowds about the Planters' House were all more or less rebel. There was also a camp in Lindell's Grove, at the end of Olive Street, under command of General D. M. Frost, a Northern man, a graduate of "West Point, in open sympathy with the Southern leaders. This camp was nominally a State camp of instruction, but, beyond doubt, was in the interest of the Southern cause, designed to be used against the national authority in the event of the General Government's attempting to coerce the Southern Confederacy.

On May 9th, Sherman would take his children with him to visit the St. Louis Arsenal and described the scene that day:

Within the arsenal wall were drawn up in parallel lines four regiments of the “Home Guards,” and I saw men distributing cartridges to the boxes. I also saw General Lyon running about with his hair in the wind, his pockets full of papers, wild and irregular, but I knew him to be a man of vehement purpose and of determined action. I saw of course that it meant business, but whether for defense or offense I did not know.

The next day, Sherman, along with his son Willie, followed the crowds up to Lindell Grove and was a witness to the Camp Jackson Affair:

[That] morning I . . . heard at every corner of the streets that the "Dutch" were moving on Camp Jackson. People were barricading their houses, and men were running in that direction . . . I felt as much interest as anybody else, but staid at home, took my little son Willie, who was about seven years old, and walked up and down the pavement in front of our house, listening for the sound of musketry or cannon in the direction of Camp Jackson . . . Edging gradually up the street, I was in Olive Street just about Twelfth, when I saw a man running from the direction of Camp Jackson at full speed, calling, as he went, “They've surrendered, they've surrendered!”

A crowd of people was gathered around, calling to the prisoners by name, some hurrahing for Jeff Davis, and others encouraging the troops . . . The man had in his hand a small pistol, which he fired off, and I heard that the ball had struck the leg of one of Osterhaus's staff; the regiment stopped; there was a moment of confusion, when the soldiers of that regiment began to fire over our heads in the grove. I heard the balls cutting the leaves above our heads, and saw several men and women running in all directions, some of whom were wounded. Of course there was a general stampede. Charles Ewing threw Willie on the ground and covered him with his body. Hunter ran behind the hill, and I also threw myself on the ground. The fire ran back from the head of the regiment toward its rear, and as I saw the men reloading their pieces, I jerked Willie up, ran back with him into a gulley which covered us, lay there until I saw that the fire had ceased, and that the column was again moving on, when I took up Willie and started back for home round by way of Market Street.