Richmond,

Virginia

Includes Richmond, Mechanicsvile, Hopewell, and Appomattox.

Features - Jefferson Davis, Gabriel Prosser, Elizabeth Van Lew, Mary Richards Bowser, Ulysses S. Grant, Robert E. Lee, George B. McClellan, George G. Meade, Phillip Sheridan, Ely S. Parker

SITE

1201 E. Clay St.,

Richmond, VA 23219

804–649–1861

Access by tour group only. 18 guests /tour. Tour Calendar

Arrival - Tours begin from the gift shop located in the house’s backyard garden. Access to the garden is from the left side of house—facing the house on Clay St.

Parking is free for visitors and is available at the VCU Medical Center Parking Deck (529 N. 12th Street, Richmond, VA 23219). Parking in this deck is free for museum visitors with validation. Validations are available in the Information Center. Museum visitors should bring their parking ticket inside to get them validated for free.

HISTORY

1861 - 1865

Built in 1818, this National Historic Landmark served as the executive mansion and home for Confederate President Jefferson Davis, and his family from 1861–1865.

In May 1861, the capital of the Confederate States of America was moved from Montgomery, Alabama to Richmond, and President Jefferson Davis and his family vacated the First White House of the Confederacy in Montgomery and moved to the house in Richmond, which was leased by the Confederate government from the city.

The Davis family was quite young during their stay at the house. When they moved in, the family consisted of the president and first lady, six-year-old Margaret, four-year-old Jefferson Davis, Jr., and two-year-old Joseph. The two youngest Davis children, William and Varina Anne ("Winnie"), were born in the house, in 1861 and 1864, respectively. Among their neighborhood playmates was George Smith Patton, whose father commanded the 22nd Virginia Infantry, and whose son commanded the U.S. Third Army in World War Two. Joseph Davis died in the spring of 1864, after a 15-foot fall from the railing on the house's east portico. Mrs. Davis' mother and sister were occasional visitors to the Confederate executive mansion.

Davis suffered recurring bouts of malaria, facial neuralgia, cataracts (in his left eye), unhealed wounds from the Mexican War, including bone spurs in his heel, and insomnia. As a result, Davis maintained an at-home office on the second floor of the house, where his personal secretary Colonel Burton Harrison also resided. (This was not an unusual practice at the time, and the West Wing of the White House in Washington, D.C., was similarly added during the Theodore Roosevelt administration.)

The house was abandoned during the evacuation of Richmond on April 2, 1865 and within twelve hours had been seized intact by soldiers from Major General Godfrey Weitzel's XVIII Corps. President Abraham Lincoln, who was in nearby City Point (now Hopewell, Virginia), traveled up the James River to tour the captured city, and visited Davis' former residence for about three hours – although the President only toured the first floor, feeling it would be improper to visit the more private second floor of another man's home. Admiral David Dixon Porter accompanied Lincoln during the visit. They held a number of meetings with local officials in the house, including Confederate Brigadier General Joseph Reid Anderson, who owned the Tredegar Iron Works.

HISTORY

Slavery denied African Americans the education and skills required to exercise the freedom won by the Civil War. To redress that, Congress created the Freedmen’s Bureau and Freedman’s Bank in March 1865. In Richmond, the Bureau and its branch Bank first operated out of two frame buildings here at 10th and Broad Streets, relocating several times before closing in 1872 and 1874, respectively. The agencies united families, legalized marriages, and provided education, food, clothing, job placement, legal and other services to former slaves. The Bureau’s and Bank’s written records are among the earliest and most complete histories of African American heritage.

HISTORY

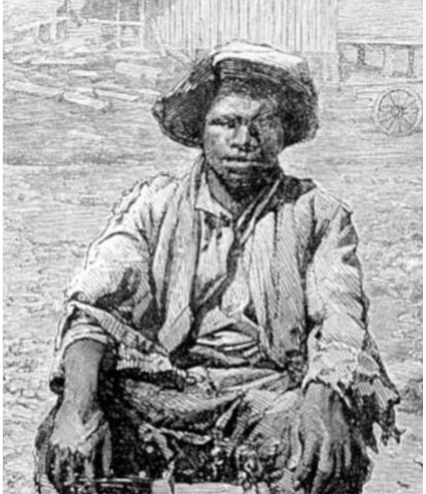

Many of Richmond’s first citizens lie in unmarked graves here. Richmond’s gallows was above on the hillside. Executed here was Gabriel, a charismatic 24-year old blacksmith from Thomas Henry Prosser’s Brookfield Plantation.

Gabriel Prosser was born into slavery in 1776, the same year the United States declared its independence from Britain. The midwife who delivered him prophesied that he would serve a great purpose in life, and his parents named him after the archangel who would herald the Second Coming. Raised on a plantation six miles north of Richmond, Virginia, Prosser grew up in bondage while white Virginians celebrated their liberty. Gabriel and his colleagues believed that Nature’s God entitled them to equal station with men and women of all races.

By 1800, Prosser had a detailed plan for a revolt known later as Gabriel’s Rebellion, in which hundreds of enslaved people from Norfolk to Charlottesville would rise up and declare their freedom too. And Prosser himself would lead a division of men to take the capital at Richmond.

Ultimately, his revolt failed before it even began due to a combination of betrayal and bad weather. The rebels were forced to postpone their plan by 24 hours. Then, a latecomer to the rebellion named Pharaoh lost his nerve. Hoping for leniency, he revealed the plot to his owner at Meadow Farm, who promptly alerted the militia and sent word to Governor James Monroe in Richmond.

Twenty-six of the rebels would be hanged in the aftermath of the plot’s discovery. Gabriel was the last to be hanged when he was executed alone near the city’s slave jail in an area that is now a parking lot next to the interstate. His efforts terrified slaveholders and provided a symbol for enslaved people throughout the young country.

HISTORY

Lumpkin’s Jail was owned by Robert Lumpkin, whose compound included lodging for slave traders, a slave holding facility, an auction house, and a residence for his family. Enslaved Africans held for auction at Lumpkin's Jail referred to it as "the Devil's Half Acre." In 1867 Mary Lumpkin, a black woman who was his widow, rented the complex to a Christian school, a predecessor institution of Virginia Union University.

Most likely built at the end of the Civil War for a former slave, Emily Winfree, by her former owner, David Winfree, this two room cottage represents a typical slave quarter in which two families occupied a single dwelling. Accounts suggest that Emily raised her five children, fathered by David, in one room, while renting out the other.

Just north of here, on the northeast corner of Franklin and Mayo Streets, was the Odd Fellows Hall. In its basement, below a venue where operas, dance ensembles, and even midget acts performed, was a frequent site of slave auctions in the 1840’s and 1850’s. A red flag on the basement door indicated that sales were about to take place. The Odd Fellows had been established in England as an inter-racial philanthropic organization. Not so in Richmond.

Identical statues in Liverpool, England; Benin, Africa; and Richmond, Virginia memorialize the British, African, and American triangular trade route, now identified as the Reconciliation Triangle. President Mathieu Kerekou of the Republic of Benin apologized for his nation’s part in the trade in 1999, as did the Liverpool City Council. Virginia’s General Assembly expressed profound regret in 2007 and the governor unveiled this statue with a crowd of thousands of Richmonders.

The auction houses in Shockoe Bottom frequently sold human “goods’ along with corn, coffee, and other commodities. Slave commerce was concentrated in the roughly 30-block area bounded by Broad, 15th, and 19th Streets and the river. Davenport & Co., located at 15th and Cary streets, was an auction house near the center of the district; portions of the building survived Civil War destruction and are now a part of the present building.

HISTORY

Libby Prison was a Confederate prison at Richmond, Virginia, during the American Civil War. In 1862 it was designated to hold officer prisoners from the Union Army, taking in numbers from the nearby Seven Days battles (in which nearly 16,000 Union men and officers had been killed, wounded, or captured between June 25 and July 1 alone) and other conflicts of the Union's Peninsular campaign to take Richmond and end the war only a year after it had begun. As the conflict wore on the prison gained an infamous reputation for the overcrowded and harsh conditions. Prisoners suffered high mortality from disease and malnutrition. By 1863, one thousand prisoners were crowded into large open rooms on two floors, with open, barred windows leaving them exposed to weather and temperature extremes.

The building was built before the war as a tobacco warehouse and then used for food and groceries before being converted to a prison. In 1889, Charles F. Gunther moved the structure to Chicago and renovated it as a war museum. A decade later, the Coliseum Company dismantled the building and sold its pieces as souvenirs.

Wikipedia

Encyclopedia Virginia

SITE

37° 31.88′ N, 77° 25.248′ W. Marker is in Richmond, Virginia, in Church Hill.

Marker is on East Grace Street near North 24th Street, on the right when traveling east.

HISTORY

1861 - 1865

Richmond mayor Dr. John Adams built a mansion here in 1802. It became the residence of Elizabeth Van Lew (1818-1900) whose father obtained it in 1836. During the Civil War, Elizabeth Van Lew led a Union espionage operation. African Americans, such as Van Lew's associate Mary Jane Richards served in Richmond's Unionist underground.

Van Lew served as postmaster of Richmond from 1869 to 1877. Maggie Lena Walker, nationally known African American businesswoman, banker, and leader of the Independent Order of St. Luke, was born here by 1867. The house was razed in 1911 and in 1912 the Bellevue School was erected in its place.

ELIZABETH VAN LEW

An opponent of slavery, she helped the Union by running a successful spy ring in Richmond and in later years championed women's suffrage.

Marker is on East Grace Street just west of North 24th Street, on the right when traveling east

MARY RICHARDS BOWSER

Freed slave of the Van Lew family and indispensable partner to Elizabeth Van Lew in her pro-Union espionage work, she worked at the Confederate White House gathering and passing on military intelligence to the Union through Van Lew to General Grant.

Marker is on East Grace Street just west of North 24th Street, on the right when traveling east.

SITE

3215 East Broad Street

Richmond, VA 23223

Wed - Sun, 9am-4:30pm

The museum focuses on the Confederate medical story and contains exhibits on medical equipment and hospital life, including information on the men and women who staffed Chimborazo hospital.

HISTORY

Chimborazo became one of the Civil War's largest military hospitals. When completed it contained more than 100 wards, a bakery and even a brewery. Although the hospital no longer exists, a museum on the same grounds contains original medical instruments and personal artifacts. Other displays included a scale model of the hospital and a short film on medical and surgical practices and the caregivers that comforted the sick and wounded.

DAY 2 - BATTLEFIELD TOUR

Travel to Mechanicsville, Petersburg, and Hopewell.

SITE

Cold Harbor Battlefield and Visitor Center

5515 Anderson-Wright Dr.

Mechanicsville, VA 23111

(804) 730-5025

The trails at Cold Harbor consist of three connected loops where visitors can wander through native forest, listening to the trickle of Bloody Run creek, and learn about the site's Civil War history. The blue trail is a one-mile walk, the white trail adds an additional 1.5 miles and the yellow loop an additional 0.9 miles. These three trail segments twist through critical battlefield land. Highlights include multiple layers of original fortifications, a stop at the 2nd Connecticut Heavy Artillery monument and details on the heavy fighting that occurred in those woods on both June 1 and June 3, 1864.

Picnic - No dining at the NPS site. There are picnic facilities at the adjacent Hanover County Cold Harbor Battlefield Park.

Cold Harbor Battlefield Park Garthright House

6005 Cold Harbor Rd.

Mechanicsville, VA 23111

Hanover County Facilities Page

HISTORY

Battle of Cold Harbor - May 31 – June 12, 1864

The Overland Campaign - May – June 1864

Cold Harbor is the best known battlefield in the park. For two weeks, May 31 – June 12, 1864, the armies of Robert E. Lee and Ulysses S. Grant tangled in a complicated series of actions. A determined Confederate defense turned away a massive Federal attack on June 3 and helped convince Grant to maneuver south and advance on Petersburg. The visitor center includes a digital map program for Cold Harbor and Gaines' Mill, exhibits, and a small bookstore. A one-mile drive parallels and crosses significant stretches of both the Confederate and Union entrenchments, all of which are original to 1864. A series of walking trails, ranging from one mile to nearly three miles, takes visitors through the site.

NPS History Page

ABT History Page

Wikipedia

COLD HARBOR DRIVING TOUR

Visitors Center

Confederate troops established a defensive position near here following Sheridan's cavalry attack on May 31 and again reformed here after repulsing the Union infantry charge of June 1. The gap between Hoke's and Kershaw's Confederate divisions was about 300 yards farther along the tour road. East of the visitor center, on both sides of Rt. 156, are the fields over which Wright's Federal VI Corps attacked on June 3. From here the Confederate battle line extended north over 4 miles and south across Route 156 for 1.5 miles before anchoring on the Chickahominy River.

Confederate Turnout

These breastworks were dug and manned by troops of Confederate Lieutenant General Richard Anderson's First Corps. On the evening of June 1, Hoke's and Kershaw's men fell back to this final position. On June 3 the left flank of the Union XVIII Corps and the right flank of the VI Corps attacked this site. Ravines to the north and south split the Union attack columns and funneled them into murderous fields of Confederate crossfire.

Union Turnout

Between the turnouts, the battlefield resembles its 1864 appearance - battle lines separated by open pine woods. The earthworks along the wood line mark the high water mark of the June 3 attacks. Being unable to advance or retreat, Union soldiers fell to the ground and dug shallow trenches for cover. As the days passed these works became the main Federal trench line. In this area Union and Confederate soldiers found themselves just 200 yards apart.

Route 156

Known as Cold Harbor Road, Route 156 was the main road between Mechanicsville and Seven Pines. Old Cold Harbor Crossroads, 1/2 mile east of here, was a valuable prize for the Federal army if Grant was to threaten Richmond.

Cold Harbor National Cemetery

This small cemetery contains the remains of more than 2,000 Union soldiers, over 1,300 of them unknown. Four other National Cemeteries near Richmond - Seven Pines, Glendale, Fort Harrison and Richmond - were created by an act of Congress to honor those Union soldiers who died while in service to their country. Approximately 30,000 Confederate war dead are buried at Oakwood and Hollywood Cemeteries in Richmond.

Garthright House

After June 3 the Garthright house was behind the line of Wright's Federal VI Corps. For ten days Union surgeons used the house as a field hospital. During the battle members of the Garthright family sought shelter in the basement.

SITE

6283 Watt House Road

Mechanicsville, VA 23111

NPS Trail Map / Tour Stops PDF

HISTORY

On June 27, 1862 Union and Confederate soldiers fought the bloodiest battle of the Seven Days. In one day 15,000 men fell killed, wounded or captured. The historic Watt House still stands and served as Union General Fitz John Porter's headquarters. Follow the one-mile walking trail along Boatswain Creek past the site where Hood's Texas Brigade broke through the line and helped force the collapse of the Union position. Along the trail are historic markers, a monument to General Wilcox's Alabama brigade and a battlefield overlook that reveals a landscape little changed since the battle.

NPS History Page

ABT History Page

SITE

This 2,700 acre park contains a 16-stop driving tour which takes visitors through all four units of Petersburg National Battlefield: General Grant's Headquarters at City Point (present day Hopewell), Virginia; The Eastern Front (where the initial assaults and the Battles of the Crater and Fort Stedman occurred); the Western Front, where intense fighting continued as Grant's Army encircled the city struggling to destroy the last of Lee's supply lines; and the Five Forks Battlefield, a battle in which the outcome would eventually lead to the Confederates' retreat to Appomattox.

The best place to begin your visit is the Eastern Front Visitor Center where you can view an overview video which will help you gain a general understanding of this 292 day event. The displays and artifacts within the visitor center provide insight into how intense the fighting was at Petersburg, as well as how miserable life was for soldiers living in trenches. After exploring the visitor center, you can continue down the park's four mile tour road where you will have the opportunity to walk on the same grounds where soldiers, including Native Americans, Blacks, and Whites, all fought for the fate of their nation.

HISTORY

Prologue

Between May and mid-June of 1864, the United States army, under General Ulysses S. Grant, and the Confederate army, under General Robert E. Lee, engaged in a series of hard-fought battles in what is now called the Overland Campaign. Cold Harbor was the last battle of this campaign and was a crushing Federal loss. This forced Grant to abandon his plan to capture Richmond by direct assault. Only twenty-five miles south of Richmond, Petersburg was an important supply center to the Confederate capital. With its five railroad lines and critical roads, Grant and Lee knew that if these were cut, Petersburg could no longer supply Richmond with much-needed supplies and subsistence. Without this, Lee would be forced to leave both cities.

Grant Pivots

Grant pulls his army out of Cold Harbor and crosses the James River towards Petersburg. For several days Lee does not believe Grant's main target is Petersburg and so keeps most of his army around Richmond. Between June 15-18, 1864, Grant threw his forces against Petersburg, and it may have fallen if it were not for the Federal commanders failing to press their advantage and the defense put up by the few Confederates holding the lines. Lee finally arrives on June 18, and after four days of combat with no success, Grant begins siege operations.

The Siege

The longest siege in American warfare unfolded methodically. For nearly every attack the Federals made around Petersburg, another was made at Richmond, which strained the Confederate's manpower and resources. Through this strategy, Grant's army gradually and relentlessly worked to encircle Petersburg and cut Lee's supply lines from the south. For the Confederates, it was ten months of hanging on, hoping the people of the North would tire of the war. For soldiers of both armies, it was ten months of rifle bullets, artillery, and mortar shells, relieved only by rear-area tedium, drill and more drill, salt pork and corn meal, burned beans, and bad coffee.

By October 1864, Grant had cut off the Weldon Railroad and continued west to further tighten the noose around Petersburg. The approach of winter brought a general halt to activities. Still, there was everyday skirmishing, sniper fire, and mortar shelling. In early February 1865, Lee had only 45,000 soldiers to oppose Grant's force of 110,000 men. Grant extended his lines southwesterly to Hatcher's Run, forcing Lee to lengthen his thinly stretched defenses. By mid-March, it was apparent to Lee that Grant's superior force would either get around the Confederate right flank or pierce the line somewhere along its 37-mile length. The Confederate commanders hoped to break the Federal stranglehold on Petersburg by a surprise attack on Grant. The result was a Confederate loss at Fort Stedman, which would be Lee's last grand offensive of the war.

The End

With victory near, Grant unleashed General Phillip Sheridan at Five Forks on April 1, 1865. His objective was the South Side Railroad, the last rail line into Petersburg. With the V Corps, Sheridan smashed the Confederate forces under General George Pickett and opened access to the tracks beyond. On April 2, Grant ordered an all-out assault, and Lee's right flank crumbled. A Homeric defense at Confederate Fort Gregg saved Lee from possible street fighting in Petersburg. On the night of April 2, Lee evacuated Petersburg. The final surrender at Appomattox Court House was but a week away.

EASTERN FRONT UNIT DRIVING TOUR

5001 Siege Road

Petersburg, VA

(804) 732-3531 ext.200

NPS Driving Tour Overview

NPS Trail Map PDF

The Eastern Front Tour Road is 4-miles, one-way, and has eight stops encompassing the first couple months of General Grant's assault on Petersburg in 1864.

SITE

1001 Pecan Avenue

Hopewell, VA

(804) 458-9504

HISTORY

The Eppes family established the Appomattox plantation and their home here as early as 1635, until 1976. In 1864, General Grant and the U.S. Army used City Point as its headquarters to supply the army during the Petersburg Campaign.

On the land between the Appomattox River and the James River was the Eppes' family home and plantation, and later General Grant's headquarters site during the Petersburg Campaign.

The Appomattox Plantation was occupied by Dr. Richard Eppes and his family until 1862 when the arrival of Union gunboats on the James River convinced them to move to Petersburg. Their home served as offices for the U.S. Quartermaster and his staff during the siege.

When General Grant arrived at City Point on June 15th, 1864, Grant's headquarters was in a tent on the east lawn of the Eppes' family plantation. The cabin was built in November 1864 and is the only remaining structure from a series of 22 log cabins erected for Grant and his staff. Grant's wife and son Jesse stayed with him during the last three months of the siege.

DAY 3 - RICHMOND + APPOMATTOX

Begin in Richmond, then travel to Appomattox.

SITE

480 Tredegar St.,

Richmond, VA 23219

Daily 10am - 5pm

804-649-1861 ext 100

HISTORY

The Tredegar Iron Works in Richmond, Virginia, was the biggest ironworks in the Confederacy during the American Civil War, and a significant factor in the decision to make Richmond its capital.

Tredegar supplied about half the artillery used by the Confederate States Army, as well as the iron plating for CSS Virginia, the first Confederate ironclad warship, which fought in the historic Battle of Hampton Roads in March 1862. The works avoided destruction by troops during the evacuation of the city, and continued production through the mid-20th century.

SITE

9175 Willis Church Road

Richmond, VA 23231

NPS Trail Map / Tour Stops PDF

HISTORY

On July 1, 1862, a large portion of the Confederate army made poorly coordinated attacks up the slope of Malvern Hill into the face of a strong Union defense. The power of the Federal artillery and the natural strength of the hill contributed to the Confederate defeat in the final battle of the Seven Days Campaign. Today Malvern Hill is the best preserved battlefield in the Richmond area. An extensive walking trail covering nearly two miles has access from two parking lots, allowing visitors to examine the site from nearly every perspective. An audio podcast walking tour is available by following the links at this website.

SITE

Appomattox National Historic Park

111 National Park Drive

Appomattox, VA 24522

Daily, 9am - 5pm

Picnic - There is a set of picnic tables at the main entrance of the park to the right of the flag pole.

The reconstructed Appomattox Courthouse building houses the park's visitor center. The original courthouse burned down in 1892 and was rebuilt in 1964 as the visitor center. Ask the staff here to help you plan your park visit, pick up brochures on local attractions and key Civil War subjects, learn more in the park's exhibits, and watch the park's 17-minute orientation film, "With Malice Toward None."

McLean House - The house is open and staffed daily from 9:00-5:00 during the warm season. During winter months when visitation is slow, staff lead guided tours of the house are scheduled several times throughout the day.

NPS Landing Page

NPS Ranger Talks

NPS Hiking Trails

HISTORY

General Robert E. Lee surrendered the Army of Northern Virginia to General Ulysses S. Grant in the McLean House parlor on April 9, 1865. This event marked the beginning of the end of the Civil War.

Dressed in his ceremonial uniform (according to himself, "I may be taken prisoner today. I must look my best."), Lee waited for Grant to arrive.

Grant, whose headache had ended when he received Lee's note, arrived at the McLean house in a mud-spattered uniform—a government-issue sack coat with trousers tucked into muddy boots, no sidearms, and with only his tarnished shoulder straps showing his rank.

It was the first time the two men had seen each other face-to-face in almost two decades. Suddenly overcome with sadness, Grant found it hard to get to the point of the meeting, and instead the two generals briefly discussed their only previous encounter, during the Mexican–American War. Lee brought the attention back to the issue at hand, and Grant offered the same terms he had before:

In accordance with the substance of my letter to you of the 8th inst., I propose to receive the surrender of the Army of N. Va. on the following terms, to wit: Rolls of all the officers and men to be made in duplicate. One copy to be given to an officer designated by me, the other to be retained by such officer or officers as you may designate. The officers to give their individual paroles not to take up arms against the Government of the United States until properly exchanged, and each company or regimental commander sign a like parole for the men of their commands. The arms, artillery and public property to be parked and stacked, and turned over to the officer appointed by me to receive them. This will not embrace the side-arms of the officers, nor their private horses or baggage. This done, each officer and man will be allowed to return to their homes, not to be disturbed by United States authority so long as they observe their paroles and the laws in force where they may reside.

The terms were as generous as Lee could hope for; his men would not be imprisoned or prosecuted for treason. Officers were allowed to keep their sidearms, horses, and personal baggage. In addition to his terms, Grant also allowed the defeated men to take home their horses and mules to carry out the spring planting, and provided Lee with a supply of food rations for his starving army; Lee said it would have a very happy effect among the men and do much toward reconciling the country.

The terms of the surrender were recorded in a document handwritten by Grant's adjutant, Ely S. Parker, a Native American of the Seneca tribe, and completed around 4 p.m., April 9. Lee, upon discovering Parker to be a Seneca, remarked "It is good to have one real American here." Parker replied, "Sir, we are all Americans."

As Lee left the house and rode away, Grant's men began cheering in celebration, but Grant ordered an immediate stop. "I at once sent word, however, to have it stopped", he said. "The Confederates were now our countrymen, and we did not want to exult over their downfall", he said.

Grant soon visited the Confederate army, and then he and Lee sat on the McLean home's porch and met with visitors such as Longstreet and George Pickett before the two men left for their capitals.

The McLean House was originally constructed in 1848 as the guest house for the Raine Tavern. This house was disassembled in 1893. The group that bought the house considered rebuilding it at the Chicago World's Fair, but changed their minds and planned to re-build it in Washington, D.C. so that more people could see it. The investors involved in the move went bankrupt so the disassembled house never left Appomattox Court House. The house materials laid in the yard unprotected for over 50 years. When the home was rebuilt in 1948, only 5500 bricks remained. Most of these bricks are between the two windows on the front of the house.

EAST VILLAGE

The eastern portion of the village includes the Kelley/Robinson house, signs to mark the Confederate Stacking of Arms, and the location where Lee and Grant met again on April 10. A ranger is stationed at the East End of the village on most weekends during the summer to share these stories, including the life of John Robinson, who helped found the first African American church in Appomattox after he was emancipated. Visitors can also learn about the second meeting between Grant and Lee on April 10, 1865 and the Gordon/Chamberlain salute that started the formal surrender of Confederate infantry arms and flags on April 12, 1865.