Harpers Ferry,

West Virginia

HISTORY - JOHN BROWN'S HARPERS FERRY RAID

John Brown said that in working to free the enslaved, he was following Christian ethics, including the Golden Rule, and the Declaration of Independence, which states that "all men are created equal". He stated that in his view, these two principles "meant the same thing".

Brown first gained national attention when he led anti-slavery volunteers and his sons during the Bleeding Kansas crisis of the late 1850s, a state-level civil war over whether Kansas would enter the Union as a slave state or a free state. He was dissatisfied with abolitionist pacifism, saying of pacifists, "These men are all talk. What we need is action – action!" In May 1856, Brown and his sons killed five supporters of slavery in the Pottawatomie massacre, a response to the sacking of Lawrence by pro-slavery forces. Brown then commanded anti-slavery forces at the Battle of Black Jack and the Battle of Osawatomie.

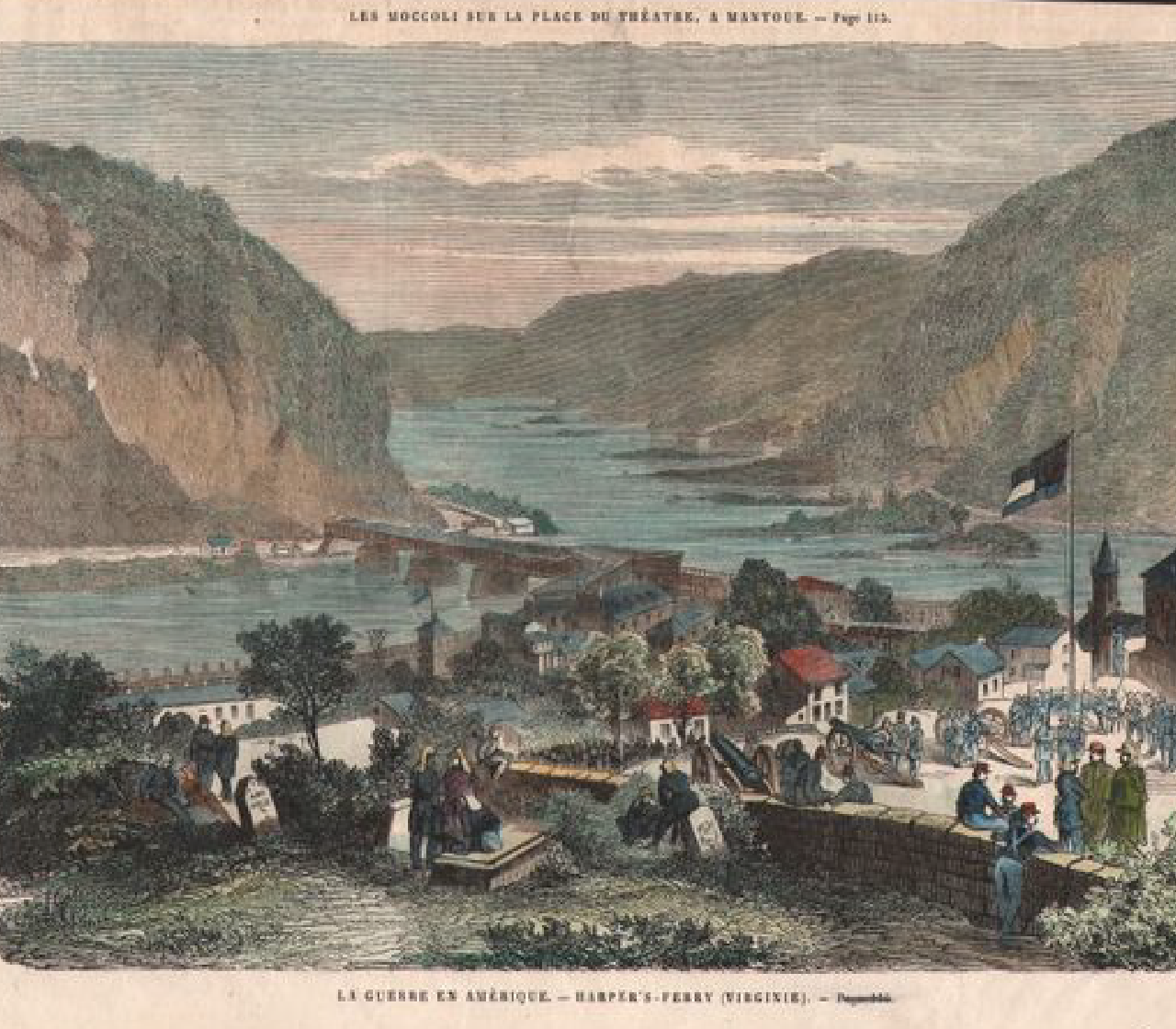

In October 1859, Brown led a raid on the federal armory at Harpers Ferry, Virginia (which became West Virginia), intending to start a slave liberation movement that would spread south; he had prepared a Provisional Constitution for the revised, slavery-free United States that he hoped to bring about.

Brown's party of 22 was defeated by a company of U.S. Marines, led by First Lieutenant Israel Greene. Ten of the raiders were killed during the raid, seven were tried and executed afterwards, and five escaped.

Several of those present at the raid would later be involved in the Civil War: Colonel Robert E. Lee was in overall command of the operation to retake the arsenal. Stonewall Jackson and Jeb Stuart were among the troops guarding the arrested Brown, and John Wilkes Booth was a spectator at Brown's execution.

The raid was extensively covered in the press nationwide—it was the first such national crisis to be publicized using the new electrical telegraph. Reporters were on the first train leaving for Harpers Ferry after news of the raid was received, at 4 p.m. on Monday, October 17. It carried Maryland militia, and parked on the Maryland side of the Harpers Ferry bridge, just 3 miles (4.8 km) east of the town (at the hamlet of Sandy Hook, Maryland). As there were few official messages to send or receive, the telegraph carried on the next train, connected to the cut telegraph wires, was "given up to reporters", who "are in force strong as military". By Tuesday morning the telegraph line had been repaired, and there were reporters from The New York Times "and other distant papers".

John Brown had originally asked Harriet Tubman and Frederick Douglass, both of whom he had met in his transformative years as an abolitionist in Springfield, Massachusetts, to join him in his raid, but Tubman was prevented by illness and Douglass declined, as he believed Brown's plan was suicidal.

“John Brown's zeal in the cause of freedom was infinitely superior to mine. Mine was as the taper light; his was as the burning sun. I could live for the slave; John Brown could die for him.”

- Frederick Douglass

Brown's raid caused much excitement and anxiety throughout the United States, with the South seeing it as a threat to slavery and thus their way of life, and some in the North perceiving it as a bold abolitionist action. At first it was generally viewed as madness, the work of a fanatic. It was Brown's words and letters after the raid and at his trial – Virginia v. John Brown – aided by the writings of supporters, including Henry David Thoreau, that turned him into a hero and icon for the Union.

“…I wish I could say that Brown was the representative of the North. He was a superior man. He did not value his bodily life in comparison with ideal things. He did not recognize unjust human laws, but resisted them … No man in America has ever stood up so persistently and effectively for the dignity of human nature… He needed no babbling lawyer… to defend him. He was more than a match for all the judges… He could not have been tried by a jury of his peers, because his peers did not exist. Do yourselves the honor to recognize him. He needs none of your respect.”

- Henry David Thoreau

John Brown’s Body

"John Brown's Body" is a United States marching song about the abolitionist John Brown. The song was popular in the Union during the American Civil War. According to an 1889 account, the original John Brown lyrics were a collective effort by a group of Union soldiers who were referring both to the famous John Brown and also, humorously, to a Sergeant John Brown of their own battalion.

Julia Ward Howe heard this song during a public review of the troops outside Washington, D.C., on Upton Hill, Virginia. Howe's companion at the review suggested to Howe that she write new words for the fighting men's song. Staying at the Willard Hotel in Washington on the night of November 18, 1861, Howe wrote the verses to the "Battle Hymn of the Republic". Of the writing of the lyrics, Howe remembered:

I went to bed that night as usual, and slept, according to my wont, quite soundly. I awoke in the gray of the morning twilight; and as I lay waiting for the dawn, the long lines of the desired poem began to twine themselves in my mind. Having thought out all the stanzas, I said to myself, "I must get up and write these verses down, lest I fall asleep again and forget them." So, with a sudden effort, I sprang out of bed, and found in the dimness an old stump of a pencil which I remembered to have used the day before. I scrawled the verses almost without looking at the paper.

Howe's "Battle Hymn of the Republic" was first published on the front page of The Atlantic Monthly of February 1862.

SITE

Harpers Ferry NHP Visitor Center

171 Shoreline Drive

Harpers Ferry, WV 25425

NPS Landing Page

NPS 1 Day Itinerary

NPS Visitors Center to Lower Town Trail

1.6 miles, 150 feet downhill, 30min-1hr

Parking - Visitors may park their vehicles and take a shuttle bus to the Lower Town district of the park. Riding the bus is included in the park entrance fee.

- The shuttle bus service operates every day that the park is open. Buses run every 10-15 minutes.

- During Eastern Standard Time (November 7, 2022 - March 12, 2023): Start at 9 a.m.; last bus runs at 5:30 p.m.

- During Daylight Saving Time (March 13, 2023 - November 5, 2023): Start at 9 a.m.; last bus runs at 7 p.m.

This quaint 19th century town is designated a National Historic District by the National Register. The architecture of the houses and shops reflect the town's history as a transportation hub 1800 - 1860, a strategic location during the Civil War, a thriving industrial center based on water power in the late 1800s. The Harpers Ferry National Historic Park offers museums, events, and tours. The Appalachian Trail courses through town as its halfway mark between Georgia and Maine.

TOURS

HP History Guided Walking Tours

NPS Harpers Ferry Civil War Landing Page

NPS 1862 Battle of Harpers Ferry Landing Page

Wikipedia

Bolivar Heights

This site offers hiking trails and great views of Harpers Ferry along with interpretive signs.

School House Ridge North & Schoolhouse Ridge South

NPS North Hiking Trail / NPS South Hiking Trail

School House Ridge North is where Stonewall Jackson positioned his troops during the Confederate attack against Union forces in Harpers Ferry. Both sites have trails and interpretive waysides for visitors to enjoy.

Murphy-Chambers Farm

This farm was a part of the Confederate attack in 1862. The site offers hiking trails with spectacular vistas, Civil War era artillery, earthworks, and interpretive waysides. This farm also was home to John Brown’s Fort from 1895 to 1909 after it was brought back to Harpers Ferry from Chicago. In 1906, members of the Niagara Movement took a pilgrimage to this site.

SITE

Visit where the Potomac and Shenandoah rivers meet! From this location, known as The Point, you look upon three states - Maryland, Virginia, and West Virginia - as well as the confluence of the two rivers. We invite you to visit in any season to gaze upon the magnificent sight of this water gap in the Blue Ridge Mountains.

HISTORY

When the Wager family, heirs to Robert Harper, sold land to the government for the Armory in 1796, one of the two parcels of land they retained was the "Ferry Lot Reservation" (the other tract was the "Six-Acre Reservation" which comprised the heart of the Lower Town). The ¾-acre "Ferry Lot Reservation" sat at the confluence of the Potomac and Shenandoah rivers, and became a bustling commercial area as the town of Harpers Ferry grew.

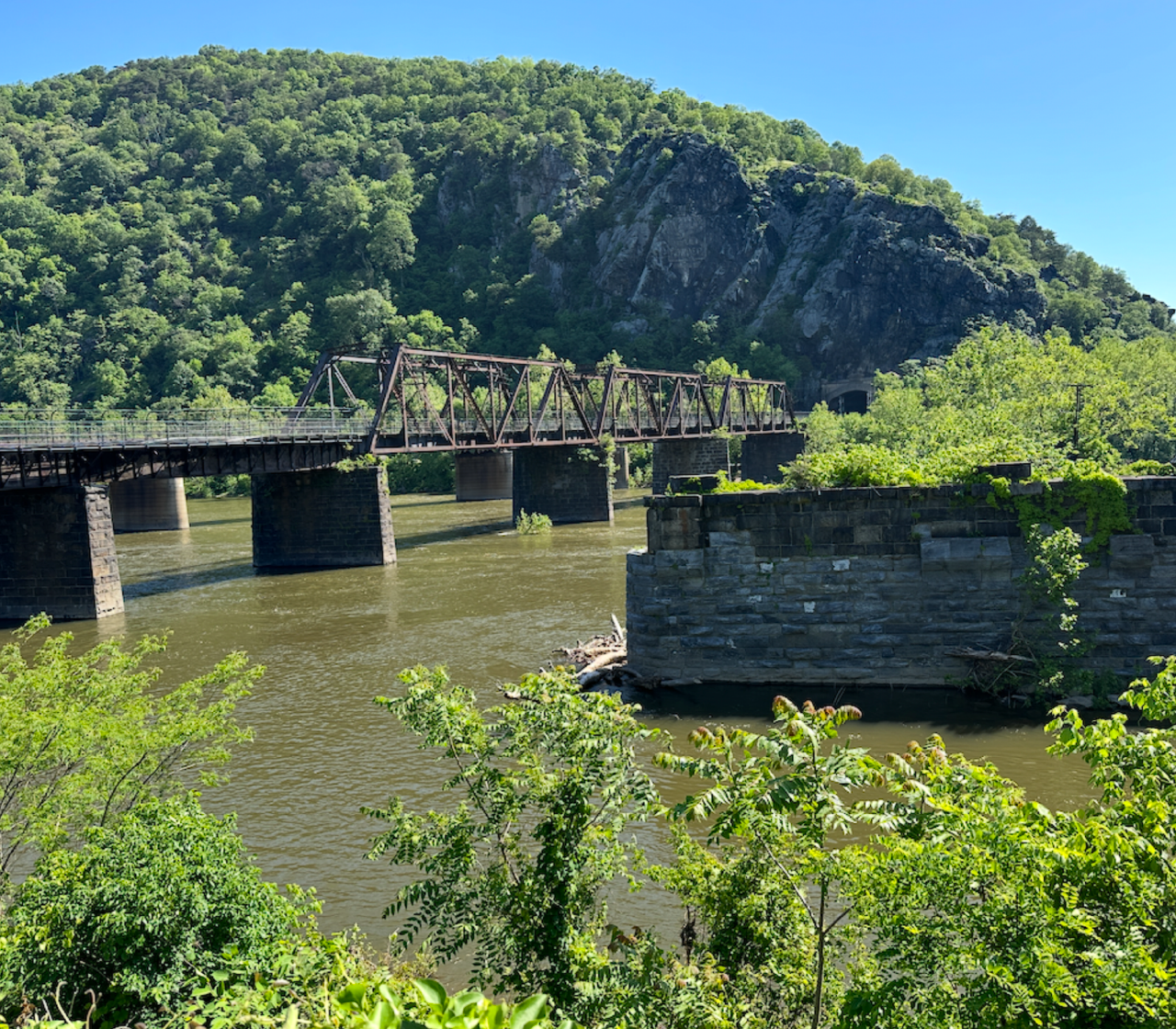

A major contributor to the prosperity of the "Ferry Lot Reservation" was the completion in 1836 of the B&O Railroad viaduct across the Potomac River. By 1859, structures at The Point included The Gault House Saloon, the Wager House Hotel, the Potomac Restaurant, and several other small shops and businesses. The B&O Railroad and Winchester & Potomac Railroad also maintained passenger depots here.

But the prosperity of the "Ferry Lot" ended with the Civil War. On June 14, 1861, Confederate troops blew up the B&O Railroad bridge. Eight months later, on February 7, 1862, Union troops burned all the buildings on The Point to prevent Confederate sharpshooters from using them for cover.

During the course of the Civil War, the railroad bridge was destroyed and replaced nine times. After 1862, the B&O Railroad began erecting new iron spans designed by Wendell Bollman. By 1870, this "Bollman Bridge" was completed. Bollman’s iron spans carried the B&O mainline until 1894, and continued to serve as a highway bridge into the present century. Floodwaters in 1924 swept away three iron spans, but these were promptly replaced. Twelve years later the record Flood of 1936 destroyed this bridge for good.

SITE

Daily, 9am - 6pm

The structure we now call John Brown’s Fort was erected in 1848 as the Armory’s fire engine and guard house. The building was described in a June 30, 1848, Armory report as “an engine and guard-house, 35½ x 24 feet, one story brick, covered with slate, and having copper gutters and down spouts, has been constructed, and is now occupied.” It was in this building that John Brown and several of his followers barricaded themselves during the final hours of their ill-fated raid of October 16, 17, and 18, 1859.

HISTORY

During the Civil War, the John Brown Fort was used as a prison, a powder magazine, and perhaps a quartermaster supply house. Union troops admired the fort as they passed while Confederate troops cursed it. Many troops broke pieces of brick and wood off the fort as souvenirs. It was the only Armory building to escape destruction during the Civil War. In 1891, the fort was sold, dismantled and transported to Chicago where it was displayed a short distance from The World’s Columbian Exposition. The building, attracting only 11 visitors in ten days, was closed, dismantled again and left on a vacant lot. In 1894, Washington, D.C. journalist Kate Field, who had a keen interest in preserving memorabilia of John Brown, spearheaded a campaign to return the fort to Harpers Ferry.

Local resident Alexander Murphy made five acres available to Miss Field for the cost of $1, and the Baltimore & Ohio Railroad offered to ship the disassembled fort to Harpers Ferry free of charge. In 1895, John Brown’s Fort was rebuilt on the Murphy Farm about three miles outside of town on a bluff overlooking the Shenandoah River. In 1903, Storer College began their own fundraising drive to acquire the structure. In 1909, on the occasion of the 50th Anniversary of John Brown’s Raid, the building was purchased and moved to the Storer College campus on Camp Hill in Harpers Ferry. It was used as a museum and many students were required to give tours of the museum to strengthen their public speaking skills. Acquired by the National Park Service in 1960, the building was moved back to the Lower Town in 1968. Because the fort’s original site was covered with a railroad embankment in 1894, the building was placed about 150 feet east of its original location.

HISTORY

Original Armory Location

The federal government constructed two arsenal buildings at Harpers Ferry to store the weapons produced at the armory. In 1859 there were 100,000 weapons stored in the arsenal buildings, which played a role in the John Brown raids. Brown intended to use firearms seized at Harpers Ferry to commence a war to end slavery, but failed to do so.

Sixteen months later, at the outbreak of the Civil War, only 15,000 weapons were stored at Harpers Ferry. The years between John Brown's raid and the Civil War, the majority of the arms at the United State Arsenal were distributed to Southern states under the instruction of Secretary of War John B. Floyd, a politician who was loyal to Southern interests.

When Virginia seceded from the Union, in 1861, Governor John Letcher ordered the Virginia militia to seize the armory and arsenal at Harpers Ferry. Captain Turner Ashby led the militia towards Harpers Ferry and once they were close they could hear an explosion. The two arsenal buildings were set ablaze by the retreating Union forces, under Lt. Roger Jones command, and 15,000 weapons were destroyed.

Close to 100 years after the Civil War, the National Park Service's archeologists discovered the original foundations of the two arsenal buildings, which were buried for generations. They also found thousands of pieces of burned weapons, which included melted and twisted barrels, bayonets, ramrods, and lock plates. Today the arsenal ruins are outlined to attain a better understanding of their role in Harpers Ferry's history.

Upon entering the John Brown Museum, visitors will get to experience a three-part film on John Brown's life before, during and after his raid in Harpers Ferry. In the break between video segments, visitors can participate in interactive exhibits and learn more details on Brown's life and actions. The second floor of this museum also contains restrooms and our Allies for Freedom exhibit.

PM - JOHN BROWN'S RAID DRIVING TOUR

5 Sites

37 miles

90 minutes

Locations:

- Sharpsburg, MD

- Charles Town, WV

SITE

Prearranged, prepaid tours are currently available for groups of 1-9 for a tax deductible donation to the John Brown Historical Foundation of $250.00. Groups of 10 or more please add $4 for each additional person. 100% of the donation goes towards the costs and maintenance of the property.

John Brown Raid Headquarters Landing Page

HISTORY

Kennedy Farm, located in Washington County, Maryland, served as John Brown’s headquarters during his 1859 raid on the federal arsenal at Harpers Ferry, Virginia (now West Virginia).

Along with a small band of followers, he rented the two-story Kennedy farmhouse, located approximately seven miles from Harpers Ferry. During the three months leading up to the raid, Brown divided his time between Chambersburg, Pennsylvania and this farm, living under the alias of Isaac Smith, a cattle buyer from New York. The Kennedy farmhouse served as the center of operations where Brown stockpiled weapons and studied local maps. He stored 15 boxes of guns and hundreds of pikes to arm future liberated enslaved recruits from the Virginia countryside.

Twenty-one men gathered at the farm in preparation for the attack just across the Potomac River. To not alarm neighbors, the men hid in the attic during the day and only emerged after dark. Brown’s family helped keep appearances by tending to the farm and household duties.

SITE

The main (1820) portion of the house is a two-story stucco-faced brick structure on a stone foundation. The corners of the three-bay house are thickened by pilasters, with a similar frieze-like thickening extending horizontally above the second floor windows. The front, or south elevation has a small portico with a flat roof and four Ionic columns. The front door has sidelights and an overlight, echoed by the second floor window immediately above the portico. The east and west ends have stepped gables with central chimneys and the "shadow" of a porch. A small 2½ story structure to the north of the main house connects to the main house with a two-story link. This structure has a gabled roof with dormers and is also stuccoed. Its windows are late 18th century in detail.

HISTORY

Lewis William Washington (November 30, 1812 – October 1, 1871) was a great-grandnephew of President George Washington. He is most remembered today for his involuntary participation in John Brown's raid on Harpers Ferry, Virginia, in 1859. He was taken as hostage and some of his slaves were briefly freed. (See Black participation in John Brown's Raid.) As he outranked the other hostages he was their unofficial spokesperson, and he testified in Brown's subsequent trial, and before the Senate committee investigating the raid.

Lewis William inherited several relics of George Washington, including a sword allegedly given by Frederick the Great to Washington and a pair of pistols given by Lafayette. John Cook, who served as John Brown's advance party at Harpers Ferry, befriended Washington and noted the relics, as well as the slave population at Beall-Air. Brown was fascinated with the Washington relics. During Brown's raid on Harpers Ferry a detachment from his force led by Cook seized the sword and pistols along with Washington at Beall-Air, taking along three of Washington's slaves. The hostages were taken to Harpers Ferry by way of the Allstadt House and Ordinary, where more hostages were taken. All survived their captivity, and Washington identified Brown to the Marine rescue party. During the assault on John Brown's Fort, a saber thrust by Marine Lieutenant Green at Brown was allegedly deflected by the belt buckle securing the Washington sword.

SITE

You may enter into the Courthouse during business hours to view part of the courtroom where the trial took place, starting on October 25, 1859.

The old Charles Town jail was torn down in 1919. It sat diagonally across from the courthouse, where the post office now sits.

HISTORY

HISTORY - Despite the fact that the raid happened on federal land, Governor Henry Wise ordered that the men be tried in Virginia. The trial began on October 27, just 9 days after Brown’s capture, and ended with the sentence of hanging on November 2. Richard Parker was judge. The defense, which was provided by the state, called no witnesses, and Brown himself did not testify. Hiram Griswold delivered the defense’s closing remarks, arguing that Brown could not be found guilty of treason against a state of which he was not a resident, that he had not personally killed anyone, and that no slaves had rebelled. The jury deliberated for only 45 minutes before issuing a verdict of guilty.

Before sentencing, Brown made the now famous statement, “Now, if it is deemed necessary that I should forfeit my life for the furtherance of the ends of justice, and mingle my blood farther with the blood of my children and the blood of millions in this slave country whose rights are disregarded by wicked, cruel, and unjust enactments, I say let it be done.”

The Charles Town courthouse was severely damaged during the Civil War. It was renovated and enlarged after the war and is open to the public.

SITE

The Gibson-Todd House was the site of the hanging of John Brown. The property is located in Charles Town, West Virginia, and includes a large Victorian style house built in 1891.

HISTORY

John Brown was hanged on December 2, 1859, shortly before noon, on what is now the lawn of the Gibson-Todd House. Among those present at Brown's hanging were Stonewall Jackson, John McCausland, J.E.B. Stuart and John Wilkes Booth. A note written by Brown read:

“Charlestown, Va. 2nd December, 1859. I John Brown am now quite certain that the crimes of this guilty land: will never be purged away; but with Blood. I had as I now think: vainly flattered myself that without very much bloodshed; it might be done.”

The house was built in 1891 by John Thomas Gibson, who led the first armed response to Harpers Ferry during Brown's raid as commander of the Virginia Militia in Jefferson County. In recognition of his services, Gibson received an original copy of Brown’s provisional constitution as well as the desk on which Brown’s death warrant was signed. Gibson went on to serve as an officer for the Confederacy. After the war he was mayor of Charles Town. When the old Jefferson County jail was demolished, Gibson saved stones from the building and built a monument to the event on the property.

The house was designed by Thomas A. Mullett, son of Alfred B. Mullett. Mullett also designed the New Opera House and the new Charles Town jail.

The Gibson-Todd home is a private residence.